Amplifying children’s voices, safety, and rights in Northern Ireland’s family court system

The Commissioner Designate for Victims of Crime hosted a round table discussion with key stakeholders across the family court system to discuss the role of a child’s voice, rights, and safety.

How has the presence of children’s voices in Northern Ireland’s family court system evolved?

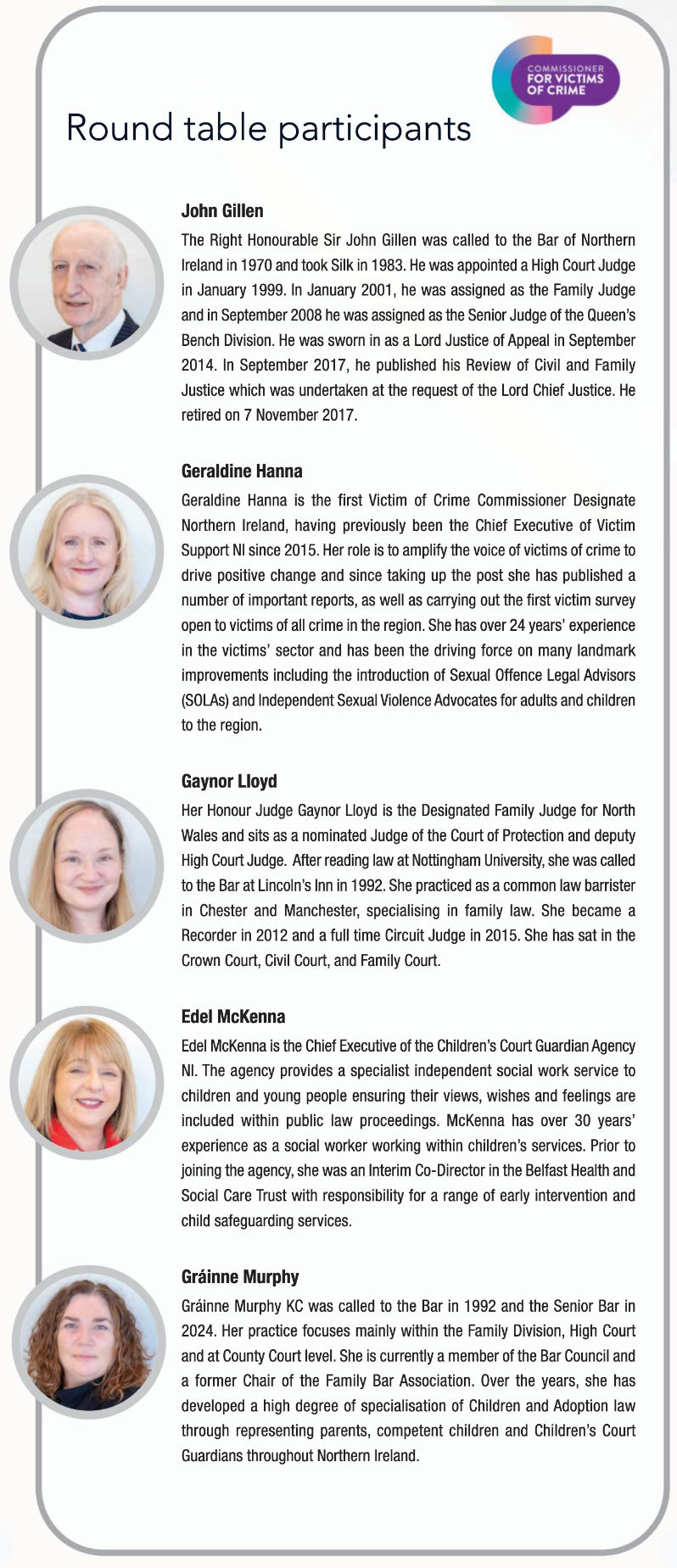

John Gillen

My review of civil and family justice in 2015 recommended the need for the voice of the child to be heard in Northern Ireland. I think that inadequate action has taken place on implementing this. There are three key considerations when assessing the evolution of children’s voices in the family court system. Firstly, progress is being stifled by the lack of resources. Secondly, we must take caution when transferring solutions from Britain to ensure they are adaptable to Northern Ireland. Thirdly, a number of longstanding weaknesses have yet to be resolved, for example, how judges speak to children and the concept of open justice when reporting judgements.

Edel McKenna

The Children’s Court Guardian Agency role is to represent the child’s best interests and ensure their wishes and feelings are made clear to the court. Over the 29 years of our existence, we have developed and improved our practice and interventions. Feedback from judiciary and solicitors, as key stakeholders, and our children and young people, has enabled us to strengthen the voice of the child. However, we cannot be complacent; there is always room for improvement. We are working in a system which is extremely pressurised. There are a multitude of challenges and we must also be determined to do better.

Geraldine Hanna

What we hear from victims of domestic abuse – as their cases go through family courts – is that there is not enough engagement with the children and their views are not being sought out. I have commissioned academics in Queen’s University Belfast to undertake research around how victims of domestic violence experience our family court system. That, I think, will help give us a better evidence base, not only in terms of children’s wishes and feelings regarding contact and their experience with their parents, but also how decisions are communicated to those children and young people.

Gaynor Lloyd

What has come through very clearly in all the research that has been done to inform the Pathfinder programme is that young people feel very strongly that their views are not being properly accounted for. They feel patronised and they want to speak directly to judges. In the Pathfinder programme, there is a presumption that children will be offered an opportunity to meet directly with the judge, and a lot of children are taking that up. We have also refined our process so that there is a requirement now in every child impact report, and in every final order, about how those decisions are going to be communicated to the child, so that there is transparency and accountability.

For us as judges, there is a qualitative difference between engaging with children in public law and private law cases, we are far more comfortable in discussing with a child any state interference in their lives, but far more squeamish about asking a child about their views on parental disputes. That is something we are trying to rectify.

Gráinne Murphy

Prior to the Children Order 1995, the courts very much relied on welfare officer reports but the Order, in trying to ensure the child’s voice is heard in public law proceedings, brought about what is now the Children’s Court Guardian Agency. In public law courts, the guardians and their solicitors are doing their best with the available resources and there is much more appreciation of the need and amount of training of judges when it comes to obtaining the voice of the child, which may include speaking directly to the child. There also is VOYPIC (voice of the young person in care) who help young people advocate their wishes. However, access to the children court’s guardians in private law proceedings is largely missing and is something that has been advocated for, for a long time. Instead of guardians, the courts dealing with private law contact/residence applications, hears the children’s voices from the parents and the Court Children’s Officers (social workers attached to the court). Occasionally, the official solicitor is appointed to represent the child. What we are seeing is resource and time pressures impacting on the child’s voice being heard independently in the private family court system.

“We are not sufficiently investigative in the way we conduct family law cases and there remains an adversarial undercurrent.”

John Gillen

What are the obstacles to improved safety and rights for children in this context?

John Gillen

The evolution of the child’s voice in Northern Ireland law has been more theoretical than practical. In my view, we are not sufficiently investigative in the way we conduct family law cases and there remains an adversarial undercurrent. There needs to be a better understanding that ‘the best interests of the child’ and the ‘child’s view’ are two different concepts and need to be treated as such. In the criminal justice system we now have SOLAs (sexual offences legal advisers) where every single victim now has a right to have a legal adviser and I think there is a role for representation of a child across the system, recognising that children have a right to have their view expressed, irrespective of whether a guardian thinks it is in their best interest or not.

Edel McKenna

The separation of court welfare services in Northern Ireland has presented a challenge for not only the judiciary and solicitors, but equally for Children’s Social Care Services and the Children’s Court Guardian Agency. One potential obstacle to improved safety and rights is the perception that a court children’s officer is perceived by a family as social services, and this can create anxiety. The Children’s Court Guardian Agency has the added advantage of being independent of all parties and is not the lead safeguarding agency. Currently, the agency is only involved in public law proceedings when directed by the court. Professor Ray Jones’ recommendation within his review of children’s social services in Northern Ireland that private law court welfare services should come in under the auspices of the Children’s Court Guardian Agency, who have the specialism, expertise and, credibility is welcome. However, this organisational change would require significant funding and resource.

Children’s Services within Trusts are facing considerable challenges linked to workload pressures, staffing shortages, and multiple competing demands. These are all contributing to delays in the court system, including private law proceedings.

“One of the greatest obstacles is the slow pace of change in Northern Ireland with regards to reform.”

Geraldine Hanna

Geraldine Hanna

One of the greatest obstacles is the slow pace of change in Northern Ireland with regards to reform. Without reform, resource continues to be a challenge across our court system. By way of example, the same support and advocacy for children does not exist in private law and we know there are ongoing challenges around remuneration for civil legal aid and increased levels of self-representation. If the quality, advice and representation for the parent is being impacted, what does that say about how we are going to learn and understand the child’s view?

Gráinne Murphy

The Re: L Court of Appeal hearing in England and Wales, which was incorporated in to our case law by Sir John was an interesting concept which essentially paused proceedings after a fact finding hearing on allegations of sexual or domestic abuse, to allow for a professional assessment on whether the perpetrator had any insight in to the impact of their behaviour on the children and whether they were willing to change their behaviour. That approach seems to have fallen out of favour and, anecdotally, what we now see in private law contact proceedings is that the court proceedings do not end until there is some form of contact. I do wonder if those decisions in the Court of Appeal if they had the same understanding and knowledge of the long-term impact domestic abuse has on children as exists today, why our courts are not investigating whether the alleged perpetrator does understand the impact of their behaviour on the parent with care and the child – and whether the voice of the child is being lost in the middle of all of this.

One of the obstacles to improved safety and rights for children is the resources available to consistently train and update the legal profession and social services in the area of domestic abuse and coercive control, and the impact of trauma on safe contact. On the judicial side, I believe there could be a specialised family court in cases where domestic abuse is raised and found to mitigate against a court system which advocates ‘moving forward’ with a case – which often means some form of contact without a full understanding of the circumstances, or importantly, hearing the voice of the child.

“More resolutions are being found because things are being considered primarily through the prism of the impact upon the child.” Gaynor Lloyd

How can the risks associated with a ‘pro-contact’ culture be best mitigated?

Geraldine Hanna

The best way to mitigate the risks of a pro-contact culture is to ensure we do not have one. Whilst pro-contact is not written in legislation, the experience of parents we have spoken to is that they feel pushed in this direction, with the safety and best interests of children not always well understood. We need to ensure that the decisions being taken are appreciative of the fact that contact should not be a binary decision.

John Gillen

I think we are insufficiently investigative. For example, in the Re: L, one of the fundamental problems is that it is based on an adversarial approach. I cannot understand why, in cases where domestic abuse is alleged, the investigative court approach does not require multi-agency reports, including from the police and the school.

Edel McKenna

The baseline has to be the safety. There are very few cases where the decision around contact is binary so we need to approach this from a training, education, and trauma-informed perspective. The system must move from a position of assumed contact to a position of what is safe and in the best interests of the child. It must take account of the child’s lived experience and its impact alongside the importance of parental relationships and this must be grounded in safety as the primary consideration.

“There are very few cases, where the decision around contact is binary, so we need to approach this from a training, education, and trauma-informed perspective.”

Edel McKenna

Gaynor Lloyd

Interestingly, in rolling out the Pathfinder programme, we expected to make a lot more ‘no contact orders’ than has been the case, and that is a uniform feature across all four pilot sites, despite very different cultural and practical circumstances. We have found that a shift in language to a more inquisitorial problem-solving approach, where we empower parents, who are best placed to understand their own family dynamic, means that more resolutions are being found because things are being considered primarily through the prism of the impact upon the child.

Gráinne Murphy

The Bar agrees that a multi-agency approach would better inform decisions taken by the court, but again, there is a challenge around resources and implementing this model. The Pathfinder programme is an interesting concept, my only concern would be whether it fully mitigates the challenge of a parent agreeing to contact because they want to get to the end of the legal process and how it manages cases effectively when domestic abuse is a factor. Our Children’s Order does not have the same pro-contact presumption as England, yet the system undoubtedly leans that way, often with proceedings not ending until overnight contact is secured. A potential mitigation is addressing the fact that the information-sharing, for example, with schools, PSNI, probation, linked criminal proceedings, which exists in public law does not happen to anywhere near the same extent in private law and so the court will have more information before making any decisions regarding contact which is in the best interests of the child.

“I believe there should be a specialised family court in cases where domestic abuse is raised and found.”

Gráinne Murphy

How might solutions, such as the pathfinder model used in England and Wales, be adapted to best meet the needs of children in Northern Ireland’s family court system?

Gaynor Lloyd

The adversarial system does not fit private law very well and does not serve families well, both during and after the proceedings. In response, many countries are attempting to deliver mediation or non-court resolution solutions but this approach was completely undermined by the Ministry of Justice’s Assessing Risk of Harm to Children and Parents in Private Law Children Cases report which recognised the harmful impact of pushing mediation on victims of domestic abuse. Pathfinder is inquisitorial in nature and adopts a multi-disciplinary approach, front-loading the work to get as much information as early as possible, which is then collated in a Child Impact Report. The model focuses on working with families and less adversarial language used in the court process to support a more problem-solving approach and a core feature is the involvement of children from the very beginning of proceedings so that in most cases the child is given the opportunity to participate in proceedings in the way they want to.

John Gillen

The key is the multi-agency, non-adversarial, child-focused approach. Breaking down silos is a key ingredient and while there are aspects of Pathfinder that might be difficult in the Northern Ireland context, the thrust of the Pathfinder concept should be introduced into Northern Ireland.

Edel McKenna

Pathfinder’s greatest asset is good practice, which leaves the courts in a much better footing to be able to make good decisions. Although we are awaiting the evaluation report of Pathfinder, everything to date is saying it is the right thing to do and I think there is a willingness in Northern Ireland to roll up our sleeves and get on with it. However, this is not just an onus on the Department of Justice, it involves many stakeholders, including health. If we want to improve our judicial system for our children and families, we have got to do better than what we are doing now. That does not necessarily mean a massive injection of new resource, albeit this will be an important component to enabling improvements, but it does mean making better use of the current resource.

Geraldine Hanna

I had the privilege of being able to go and visit the Pathfinder Dorset model with the Domestic Abuse Commissioner in England and Wales and something that really struck me was that there is faster case resolution and there are fewer cases returning. We cannot expect this approach to be a silver bullet, but, it would be ridiculous for us not to look at a model like Pathfinder, which has generated so many positive outcomes.

Gaynor Lloyd

In Wales, the average Child Arrangements Programme case was taking 35 weeks, whereas the average Pathfinder case takes 17.9 weeks. In North Wales, we have seen a reduction on average from 6.3 hearings per case to 1.8 hearings per case. We are finding that around 80 per cent of cases are resolving either by consent, without a hearing, or at that first hearing, which takes place around week 10. So, 80 per cent of children are in and out of system in 10 weeks, rather than taking several years, as many were. That allows our resources to focus then on that 15 to 20 per cent of difficult cases, where our intervention is really required.

Gráinne Murphy

I think we should put the Pathfinder programme on our family justice agenda to consider if and how it could benefit our system, as there remain differences between the law and practice between the two legal systems. I do think there is a misunderstanding about the ‘adversarial’ system in that most children’s cases are solved via negotiation outside the courtroom, with a court hearing as the last resort rather than all cases proceed to full blown evidential hearings. I am interested to hear that there remain cases that must have evidential hearings in the Pathfinder programme but that they are triaged by the court at an earlier stage in proceedings and only after there is a child impact report. If this is a system that continues to recognise and protect the Article 8 rights to family life and the child’s right to be included in decisions about them, then it should be further investigated and discussed in Northern Ireland.

What are the immediate strategic priorities to amplify children’s voices, safety, and rights in Northern Ireland’s family court system?

Gráinne Murphy

We need a cultural change whereby the Children Court Officer’s court report is more akin to the child impact reports which are directed in the Pathfinder programme. I understand that they are considered truly child-centric and focus on other aspects in a child’s life and safeguarding issues which more accurately reflects the views of the child other than a report detailing what a child says in response to questions about their living arrangements. That requires resources, training, and better access to information. I also think we need to consider if there should be a shift from the scenario where almost all contact applications run until overnight contact is achieved and instead focus on what is safe for the child at that particular moment in that particular time in the child’s life.

Gaynor Lloyd

The Pathfinder programme is incredibly effective, but it is inoperable without the independent person doing the child impact report. Resource must be available to ensure that children are being allowed to give their opinions safely and freely.

Geraldine Hanna

We need to ensure we implement Professor Ray Jones’ recommendations swiftly regarding the child advocacy role in private law. We also need to see the introduction of learnings from England and Wales, including the recently published ‘Family Justice Council Guidance on responding to a child’s unexplained reluctance, resistance or refusal to spend time with a parent and allegations of alienating behavior’, to see what improvements can be made amongst our practitioners in the court environment.

Edel McKenna

As collective stakeholders, we need to consider the Jones recommendation, which suggests ceasing the separation of court welfare services in Northern Ireland and bringing public and private law under one umbrella organisation, similar to that of Cafcass and Cafcass Cymru. Also, to be able to be the lead in terms of helping the judiciary deliver on initiatives like the Pathfinder model. However, delivery will require funding and resource.

John Gillen

We need a renewed emphasis on a non-adversarial, multi-agency approach in the family justice system and the introduction of something to similar Practice Direction 36Z.