Benchmarking Northern Ireland’s healthcare performance

The benchmarking of Northern Ireland’s healthcare system reveals a system that is grappling with an existential crisis, is not fit for purpose, and needs to evolve considerably in the coming years, the authors of a report on this area have concluded.

Originally commissioned to produce comparative information on the healthcare systems in the UK’s four jurisdictions and the Republic of Ireland, authors Austin Smyth, Sean McKay, and Alan Orme have compiled the data sets and reviewed relative performance covering five years across the five jurisdictions.

The system was struggling to meet people’s needs even before Covid-19 and the information collected around the pandemic brings into sharp focus a number of the chronic weaknesses and challenges facing the health and social care system.

The system, as currently configured is overly hospital-centric, community-based services are fragmented and there is a lack of integration within and across different services. Acute care has become the default option for many, and reactive care takes precedence over proactive, planned, and preventive care.

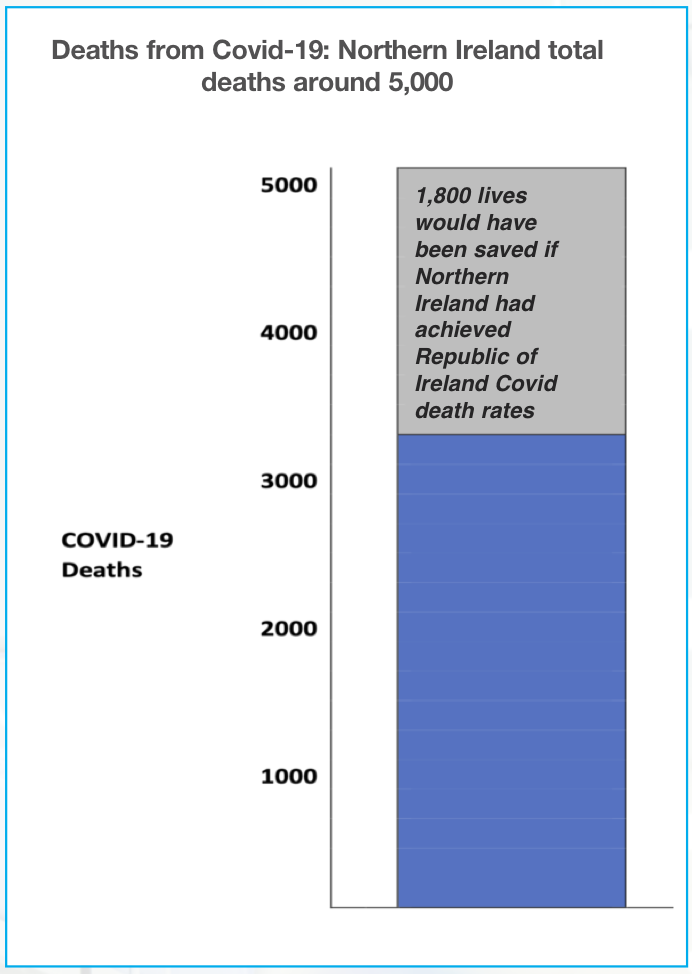

To date, around 5,000 Covid-19 deaths have been recorded in Northern Ireland. Evidence gathered during our study demonstrates that the pandemic also had several detrimental impacts on the healthcare system; for example, it dramatically reduced numbers of people presenting to A&E.

Now these people are coming forward, many with advanced illnesses. Access to GPs has fundamentally changed – there are much less face-to-face appointments. This has resulted in more people presenting to A&E departments. In many cases, these people bypassed primary care.

| In line with profiles of infection and vaccination (there were higher levels of infection and lower levels of vaccination in Northern Ireland than in the Republic of Ireland), Northern Ireland experienced death rates from Covid-19 significantly higher than the Republic of Ireland with a cumulative total of deaths equating to an overall death rate of 263 per 100,000 population in Northern Ireland in contrast to the rate of 166 per 100,000 population in the Republic of Ireland. |

A number of Covid-19 sufferers are now experiencing ‘long Covid’ typified by respiratory and mobility problems persisting for a period of more than 12 weeks.

One way of illustrating the scale of these differences is to assume the Republic of Ireland rate applied to Northern Ireland throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. If Northern Ireland’s experience had replicated the Republic of Ireland rate it would have experienced up to 1,800 fewer deaths.

Post-pandemic

Currently, post-pandemic, despite having relatively adequate resources, the healthcare system is failing the people of Northern Ireland.

Our report sought to answer two basic questions:

1. How healthy are citizens here in comparison to those in the other UK countries and the Republic of Ireland?

2. How healthy is the health system here in comparison to the other jurisdictions?

How healthy are citizens here in comparison to those in the other UK countries and the Republic of Ireland?

Evidence from our report shows that the health of citizens in Northern Ireland is being adversely affected by a number of key factors:

• face-to-face access to GPs has become more difficult;

• Since Covid-19, ambulance response times, waiting times in emergency departments, waiting times for outpatient, inpatient appointments, and diagnostic tests are by far the worst in the UK. In June 2023, figures show that the median waiting times are 105.6 weeks in Northern Ireland compared to 12.3 weeks in England. The 95th percentile wait here was 524.9 weeks, compared to England (92nd percentile) 67 weeks. This means it is possible that one unlucky patient in every 20 here could spend around 10 years from the point of being referred for an outpatient appointment until admission to hospital for treatment;

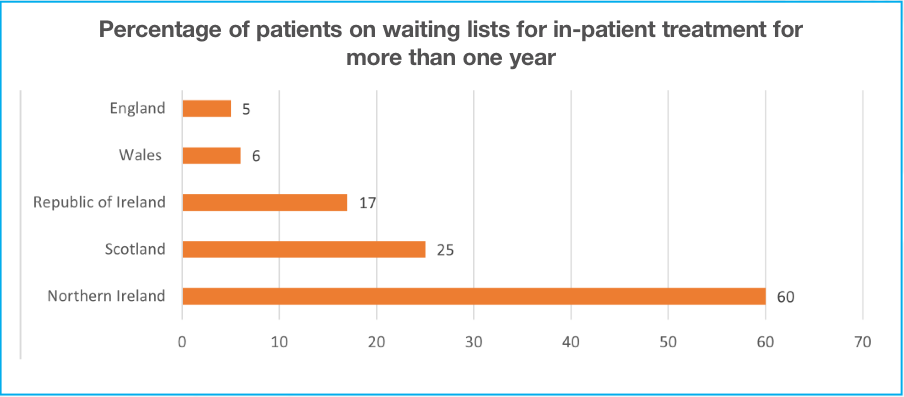

• Shockingly, 60 per cent of patients had waited more than a year for inpatient treatment in Northern Ireland at June 2023, compared to just 5 per cent of patients waiting more than a year to complete the entire pathway from referral to treatment in England;

• This means 95 per cent of people on waiting lists in Northern Ireland will have begun their treatment within 525 weeks while 92 per cent of people in England will have had their treatment completed within 67 weeks;

• cancer patients here are waiting longer than ever for treatment and cancer survival rates are not improving. For example, at June 2023, nearly nine out of 10 patients in Northern Ireland waited longer than two months to receive treatment for bowel cancer, compared to three out of 10 in Scotland. In addition, rates of lung cancer deaths in Northern Ireland are higher than the rest of the UK and Republic of Ireland; and

• immunisation rates for conditions such as flu are falling and are often lower than elsewhere in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

How healthy is the health system here in comparison to the other jurisdictions?

Evidence from our report shows that the healthcare system in Northern Ireland is also being adversely affected by a number of factors:

• patients are spending longer in hospital than required, due to a number of reasons, but primarily because of failings in the social care system; and

• despite spending more on health per capita than other UK regions, the system is inefficient. This is characterised by higher administration costs and unit costs for patient care than in similar regions in England.

Challenges

In our view, the Northern Ireland healthcare system can be improved if the Department of Health focuses its efforts on addressing the following challenges:

• Interventions to reduce the time patients spend in hospital, will be critical to improving the productivity of its healthcare system: This will require diverting adequate resources to increase access to GPs and the reduction of hospital waiting times across all service areas – out-patients, in-patients, diagnostic testing, ambulances, and emergency departments. It also requires that patients only stay in hospital until they are medically fit for discharge to home or another health setting. The social care system is not working effectively, meaning patients are ‘bed blocking’ and having a negative knock-on effect back through the system which has an adverse impact on waiting lists. The backlog cannot be cleared with one big push. It is symptomatic of a system that is struggling to cope – not providing enough care to keep up with people’s needs and managing and prioritising the situation poorly, or both;

• Improving productivity: The substantially higher staffing ratios in Northern Ireland compared to the other jurisdictions, implies there may be scope for the health service here to deliver more care with the resources its health system currently has. This suggests that at least some of the higher costs seen in comparison to other jurisdictions could be absorbed through improved efficiency. The fact that patients here spend longer in hospital than in the rest of the UK and the Republic of Ireland reinforces this point as it would appear that the treatment received by patients and their subsequent recovery takes place at a comparatively slower pace;

• Delivering healthcare in the most appropriate setting: We consider it essential that lower efficiency within the health service here is tackled urgently. This will require buy-in from health service senior management, the public, and importantly, politicians in order that the changes needed can be realised. Historically, a wide range of services have been carried out at the many small hospitals here as successive reviews have pointed out. The team considers that centres of excellence for medical and surgical procedures are more efficient and effective than the current mismatch of services provided across Northern Ireland. This may be politically unpopular, but other jurisdictions have benefited from this best-practice approach;

• Reducing the number of Health and Social Care trusts in Northern Ireland: This can free up resources to devote to improving health. Our evidence shows the provision of health trusts in Northern Ireland is more costly than for comparative health trust arrangements in other regions of a similar size. In a region the size of Northern Ireland, with a population of 1.9 million, we would question whether there is a need for five health and social care trusts. The evidence collected indicates clearly that management and administrative services are being duplicated.

Our report shows that if there was one health and social care (HSC) trust here, there could be savings in senior management team costs alone in excess of £5 million per year. These funds could be used to employ an extra 150 nurses. Allocating medical staff could also be improved under a single HSC Trust arrangement as it would be much easier to ensure a more even spread of doctors and nurses across the region.

• Developing more effective performance management: The main work of this report, to benchmark Northern Ireland’s healthcare system performance with the other UK countries and regions and the Republic of Ireland, has demonstrated that there is an ongoing need for the relevant health administrations to identify and produce a basic set of comparable health system indicators such as those the team has applied in this project. This could lead to insightful performance assessment and evaluation of management information.

In addition, we strongly believe that greater linkages between independent survey-type data collected in the areas of primary care, secondary care, and social services, along with quantitative data would enhance the types of analysis that could be undertaken. This would require an improved data infrastructure for all jurisdictions.

TAA Ltd was originally commissioned to produce comparative information on the healthcare systems in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. This information was subsequently used to produce a separate independent review of performance, written by Austin Smyth, Professor Emeritus, University of Hertfordshire and Director of TAA Ltd., Sean McKay, an ex-Director of Value For Money Studies at the NIAO and Alan Orme, a former Audit Manager of Value For Money studies at NIAO and currently a Director of AO Accountancy & Consultancy Services Limited.