We are not partying with super-parity

Lisa Wilson, senior economist at the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI), says that issues of super-parity are one of the most talked about, but misrepresented areas of public finances in Northern Ireland.

One of the most common jibes about Northern Ireland’s public finances is that it lives via the ‘begging bowl’ from the UK Government. This joke is commonplace and arises from the fact that Stormont does not really raise much cash on its own, and as a result much of its spending resources come from the UK Government.

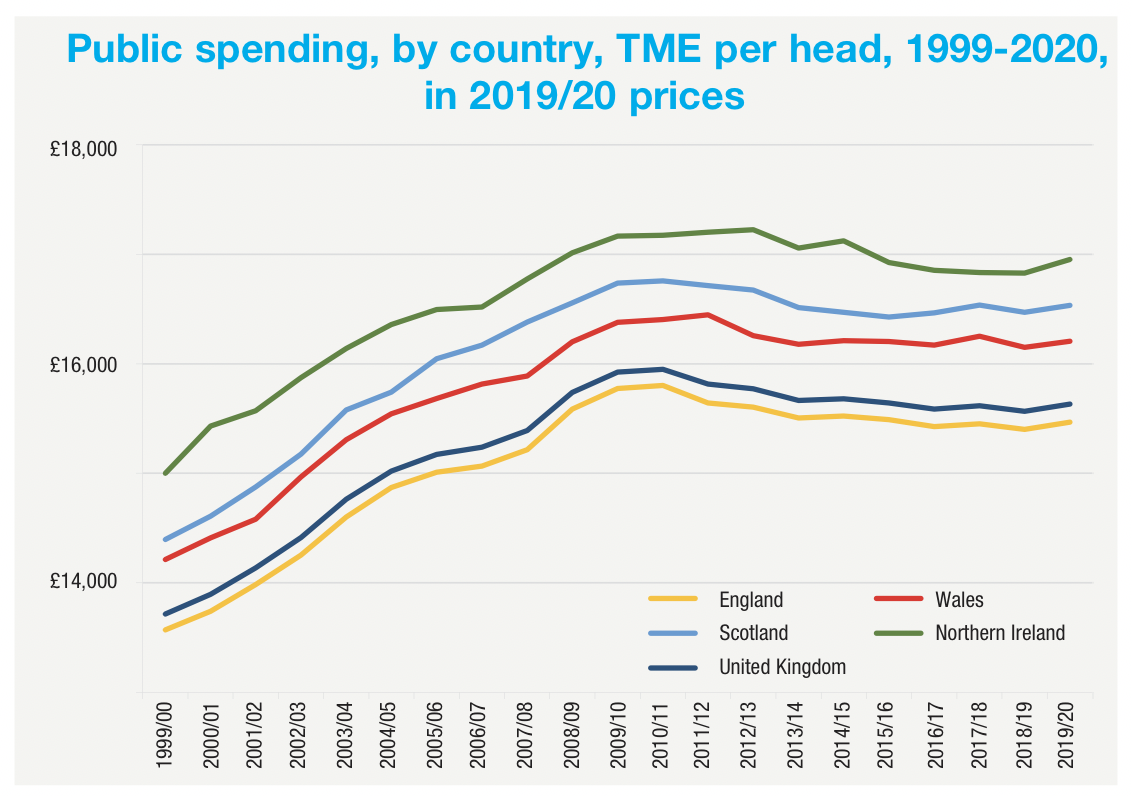

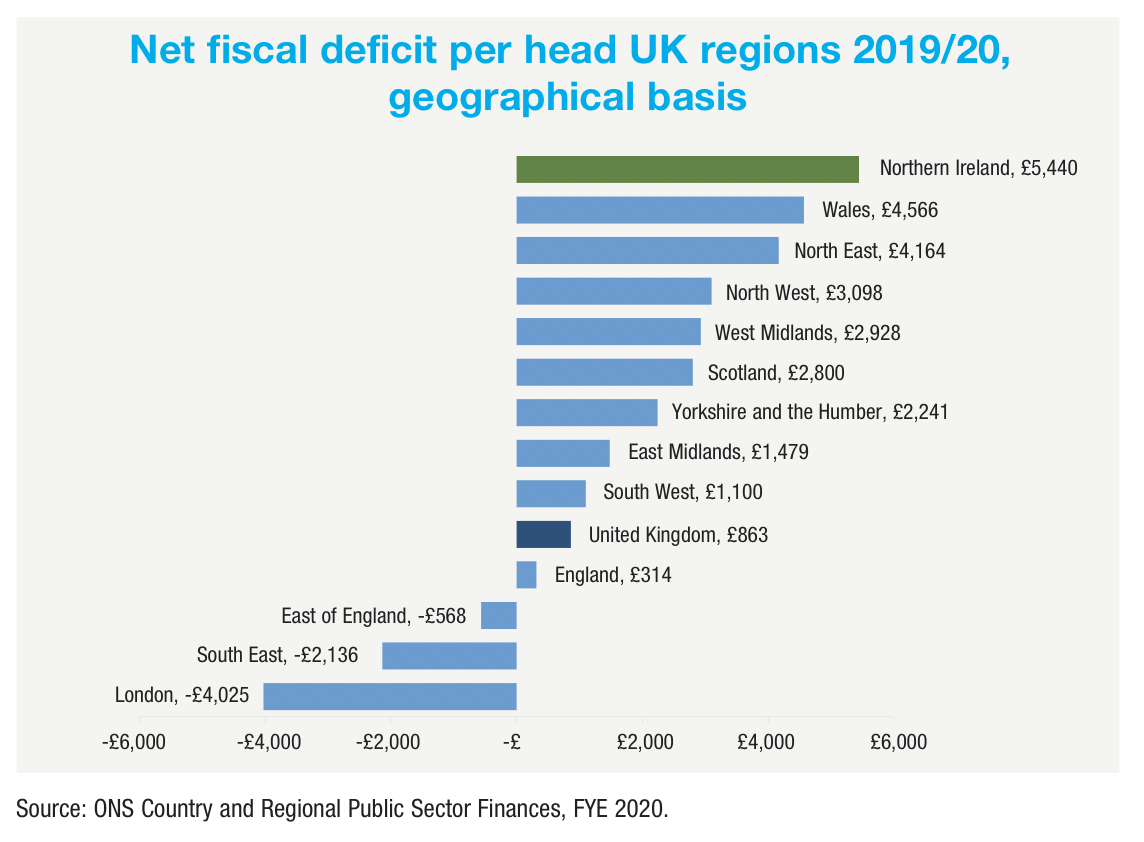

Further fuel to this fire comes from the fact that per head public spending is considerably higher in Northern Ireland than in England, and that over the years a number of supplementary budget provisions have been occasioned on Northern Ireland, tied either to intergovernmental agreements or latterly to political agreements between parties.

Recently, jibes that Northern Ireland is partying from a subsidy from the UK Government whilst not paying its fair share have again regained momentum. This has been driven by the Secretary of State who has taken a particular interest in improving the sustainability of Northern Ireland’s public finances. He is seeking advice and information on areas in which Northern Ireland could raise additional revenue or reduce expenditure if policies matched other parts of the UK. In particular, attention is being given to so-called areas of ‘super-parity’.

Super-parity refers to areas where Northern Ireland has made policy decisions to diverge and as such, forego certain streams of revenue or spend differently, compared to other parts of the UK. Areas of policy divergence include water charges, prescription charges, tuition fees, and others. Moving beyond issues of super-parity, devolution of further revenue-raising powers has been suggested as another route to help get Northern Ireland’s public finances onto a more sustainable path.

While the aim of getting Northern Ireland’s public finances onto a more sustainable path is a commendable and necessary one, questions have to be asked as to whether ending areas of policy divergence or instilling further revenue-raising powers is the right path.

One does not necessarily follow from the other, such as has been suggested by some lobby groups who on the back of Chris Heaton-Harris’ turn of focus to revenue raising, have again reinstated calls for the completion of the devolution of corporation tax. Within these calls, the central argument remains as reckless as it has always been. The central proposition goes as follows – investing in the lowering of corporation tax will lead to economic transformation – and with that, the woes of Northern Ireland’s public finances will no longer be. Sounds simple, does it not?

Similar fudge is being thrown about when it comes to the issue of water charges, where it is spoken as though fact that sums between £345 million and £615 million would be raised if water charges were implemented. This is a stretch.

Let us clarify the issue of water charges first. Issues of super-parity are perhaps one of the most talked about, but misrepresented areas of public finances in Northern Ireland.

The Independent Fiscal Commission (of which I was a member) estimated that areas of ‘super-parity’ cost Northern Ireland around £600 to £700 million in 2020/21, or some 4 per cent of the Northern Ireland Budget. £345 million was the amount allocated to water charges as taken out of the Northern Ireland Executive budget to ‘pay’ for the fact that Northern Ireland residents do not pay water charges. Specifically, the Northern Ireland Executive has extended the power for the Department for Infrastructure to pay a subsidy to NI Water, in lieu of domestic water charging since 2007.

However, when calculating the ‘cost’ of super-parity measures, it is important to recognise that the amount estimated as foregone or spent does not necessarily equate to the amount that could be raised or saved. So, if water charges were implemented, it does not necessarily follow that we would raise £345 million. The amount that would be raised would ultimately depend on the final charging model that would be applied and would have to take into consideration the fact that many households in Northern Ireland would severely struggle or be unable to pay anything at all. Such are the dire straits under which many live.

Beyond this, a point which needs to be made is that super-parity is often presented as though Northern Ireland citizens and businesses receive superior or advantageous treatment, compared to our UK counterparts. This is a misrepresentation. Although it is the case that the Executive has made policy decisions to forego certain streams of revenue, or rather, spend differently compared to other parts of the UK on these areas of super-parity, Northern Ireland does not receive additional monies to fund these. They are funded from within our existing funding allocation. We are not partying with super-parity.

Sub-parity

At the other end of the spectrum, we have ‘sub-parity’, where childcare stands out as an area that lags behind other parts of the UK. The Executive does receive a Barnett consequential as a result of UK Government spending on childcare provision which we receive through the block grant, but these monies are not currently being used to provide parity on these areas of policy.

England offers 30 hours per week of free childcare, for 38 weeks of the year to all three- and four-year-olds to all eligible working parents’ children. By September 2025, the provision will be extended and will cover all children above the age of nine months. The same provision is not available in Northern Ireland.

Going back to the devolution of further revenue-raising powers as the key to our economic transformation. The Independent Fiscal Commission for Northern Ireland recommended that if the Northern Ireland Executive was to embark on further fiscal devolution, the most appropriate place to seek to increase the revenue-raising powers of the Assembly would be via the devolution of (elements of) income tax, air passenger duty, stamp duty, and the apprenticeship levy.

However, the Independent Fiscal Commission cautioned of the risks involved in further devolution of tax-raising powers. If taxes are devolved to the Northern Ireland Executive, then the Executive’s budget will, in part, be determined by how much revenue those taxes raise in Northern Ireland. That could well lead to a more volatile budget. It could lead to the budget rising or falling, relative to what it might have been in the absence of further devolution. Given the significant gap in performance between Northern Ireland’s economy and that of the UK as a whole, these risks should be given careful consideration.

Furthermore, it does not follow that the further devolution of fiscal powers will automatically correct any of the weaknesses in the Northern Ireland economy. Devolution can assist with economic development, but the fundamental importance of the economic, social, and institutional geography of the place has to be of paramount importance.

Devolution of any tax will not act as a panacea to the economy. In this sense, it is important not to be taken in by the simplistic view that merely devolving greater fiscal powers will bring greater economic growth.

Such ‘silver bullet’ thinking is folly.