Declassified documents reveal how peace negotiations unfolded

At the end of December 2022, the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) declassified a series of papers, detailing what was taking place behind the scenes in political life in Northern Ireland through the mid-1990s.

The papers, which cover the year 1999 and the years prior, released detail the negotiations between unionists, loyalists, nationalists, republicans, and the British and Irish governments, negotiations which culminated in the Good Friday Agreement.

What has been made clear is that there was an element of unforeseen dynamism and tenacity by the late Mo Mowlam, the then-Secretary of State, as well as a cross-party approach from the British Government, with John Major and Tony Blair in frequent contact with one another. It further details the evolution of the approach of both the British and Irish governments with regard to Sinn Féin, with a key aim at the time ensuring that the Provisional IRA disbanded and decommissioned its weapons.

Mo Mowlam

As the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland from 1997, the late Mo Mowlam features prominently in the files which have been declassified.

Meetings throughout the period reveal a change in strategic outlook which took place at the heart of government in the United Kingdom regarding Ireland, including a behind-the-scenes acknowledgement of Britain’s role in the Famine in the 1840s, in addition to the role played by the British State on Bloody Sunday 1972, for which it has since officially expressed regret.

Mowlam set out her negotiating stance with Sinn Féin, outlining her belief that it ought to be accepted as a functioning democratic party with a legitimate mandate for its representatives, in the event that the party and its representatives adhered to the Mitchell principles. She further clarified in successive documents that she would never accept the Provisional IRA as a legitimate representative, although it is widely believed that, from the British Government’s perspective, when they were negotiating with Sinn Féin, that they were negotiating with the “republican movement”.

Mowlam was also a proponent of enhancing diplomatic relations between Britain and Ireland, relations which at that point were often highly strained, although she outlined in a letter to Tony Blair that this needed to be managed delicately, with a diminishing of the British-Irish Council having the potential to strain relations between the British Government and David Trimble.

Despite this, the disbandment of the RUC was seen as a non-starter from the British perspective, with Mowlam outlining in correspondence regarding upcoming negotiations with Sinn Féin that the British Government would not support such a measure, although it later became a cornerstone of the subsequent agreement.

The negotiations

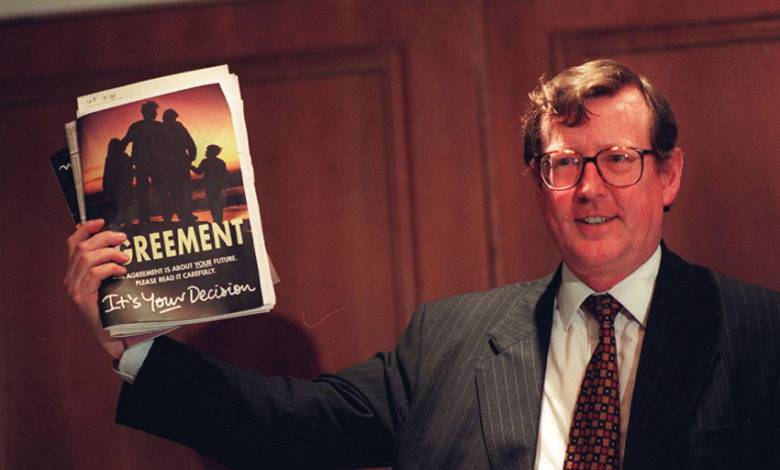

The late David Trimble, the former leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, was a key figure in ensuring that unionism came to support the Good Friday Agreement. Papers detail how he held “business-like” negotiations with former Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams, with concerns at the potential “embarrassment” at how such collaboration with republicans would be perceived by people within his own party, as well as the wider unionist electorate.

Documents further reveal a level of mutual respect between the Ulster Democratic Party (UDP), the PUP, and Sinn Féin, all of which acknowledged each other’s aspirations and praised their respective roles in persisting with the talks. However, the documents reveal that, at one point during the negotiations, Sinn Féin accused the British Government of collusion when the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) murdered two Catholic men, in order not to compromise the position of the UDP, a key loyalist stakeholder in the negotiations.

William McCrea, who now sits in the House of Lords as a DUP representative, further alluded to a “conspiracy” surrounding the circumstances of Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) leader Billy Wright, who was murdered in prison in December 1997.

Documents further reveal an assertion made by Gregory Campbell, who now sits as a DUP MP. He outlined concerns in negotiations in 1997: “I want democracy. At present we are disenfranchised. Why? Because hoods and gangsters who turned up at Downing Street manipulate thousands of votes in order to get elected, as in Mid Ulster.”

Campbell further outlined his objections to the approach to be taken with regards to the Irish language. “If a supporter of the Irish language applies for a grant, the only matter in question is the number of noughts on the cheque. That figure could be £10,000 or £100,000. I want that to be changed. Unionists have an ethos and culture which must be respected.”

A paper released by the Irish Government in May 1997 details the approach taken by its representatives when dealing with Sinn Féin. Whilst there was no blanket ban on association with Sinn Féin, a party which just eight days after this letter won its first Dáil Éireann seat since 1957 with the election of Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin, there was a ban on ministers going to an event with the expressed purpose of meeting Sinn Féin representatives, and ministers were ordered not to go out of their way to meet Sinn Féin representatives, as well as being required to have expressed permission should they have to meet a Sinn Féin member.

The papers offer a unique insight into the unique role played by Mo Mowlam in the negotiations, with her dynamic capability being highlighted in how she navigated the treacherous path of ensuring that republicans, loyalists, as well as mainstream unionists and nationalists, could be brought into a process, in addition to spearheading a thaw in relations between Britain and Ireland; measures which have helped Northern Ireland maintain a level of relative peace.