Protocol offers protection from ‘poorer and less productive’ UK by 2030

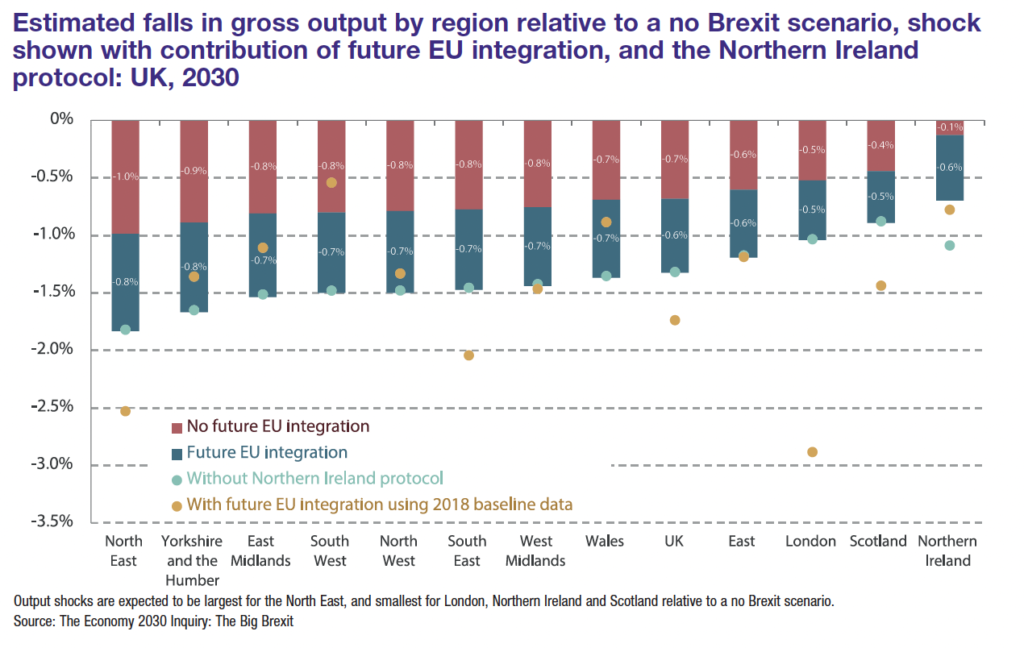

Northern Ireland will be the region of the UK to experience the least Brexit-induced economic decline due to the Protocol, academics from the London School of Economics and the Resolution Foundation think-tank have found.

Despite a reluctance by those opposed to the post-Brexit trading arrangements to identify the Protocol as the reason the economic decline witnessed across the UK has been largely averted in Northern Ireland, when compared to other regions of the UK, the Resolution Foundation’s assessment of the longer-run impacts of Brexit points primarily at the Protocol as the reason for smaller economic contraction.

Northern Ireland will experience economic decline from Brexit, with output falling by 0.7 per cent but this is significantly less than the UK average of 1.3 per cent. With the Protocol removed, it is estimated that Northern Ireland would experience a 1.1 per cent output shock.

The research is based on current implementation of the Protocol, whereby some grace periods are still in operation and so it is recognised that full implementation could have greater economic impacts.

Much economic modelling on the effect of Brexit focused on immediate shocks, specifically a significant fall off of foreign direct investment (FDI). However, the research suggests that, rather than fundamental changes to the UK economy, the main economic impacts occurring are a reduction in household incomes as a result of inflation, as well as lower levels of investment and trade.

Brexit did have immediate impacts on the UK economy. A year after the referendum, sterling was 12 per cent below its previous level and the cost of living had risen by an equivalent of £870 per year. At the same time, business investment fell consistently in the three years post-referendum by an average of 0.1 per cent per quarter compared to growth of 1.7 per cent in the previous three years.

In the longer term, immediately after the referendum, UK exports to and imports from the EU changed little. However, since the implementation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, there have been significant changes. The research is quick to point out that many of these changes took place in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, hence a focus “largely on the relative performance of UK trade with the EU relative to that with the rest of the world, or on the UK’s trade performance relative to similar economies during this exceptional period, rather than changes in the level of UK trade with the EU”.

Describing an initial perception of an overall economic impact of Brexit being “a discrete, and relatively rapid, one-off impact”, the research says that the reality is a three-phase impact.

1. The immediate referendum impact whereby household incomes and business investment were impacted by the anticipation of permanent impacts;

2. How trade responds to the new barriers introduced through the Trade and Co-operation Agreement; and

3. Structural changes to the UK economy over the longterm, as capital and labour adjust to the new trading arrangements.

“Overall, we find that the long-run impacts will mean significant change for some sectors of our economy, but the aggregate effect will be to reduce household incomes as a result of a weaker pound, and lower investment and trade,” the research suggests, although adding that while substantial, this adjustment is not expected to fundamentally alter the nature of the UK’s economy.

The report suggests that while an expected relative decline in imports and exports is not clearly observable in UK data, the data of trading partners suggests UK goods exports to the EU have fallen by more than those to the rest of the world.

Rather than view the absence of clear evidence of an expected relative decline in UK exports to the EU as good news, the report says that signals exist that Brexit is impacting UK trade openness and competitiveness more broadly. Highlighting an eight-percentage point drop in UK trade openness between 2019 and 2021, it states that the UK is the only large European country to experience a decline in openness since 2020, driven by goods trade. As a result, UK goods exports as a share of GDP were 15.7 per cent lower in December 2021 than they would have been in the absence of Brexit.

Additionally, data on trade in international goods points to a broader loss in UK competitiveness, with the UK losing market share across three of its largest non-EU goods import markets in 2021.

“It is unclear exactly how persistent these changes in non-EU trade will prove, but these are worrying signs that Brexit may have had a broader impact on the UK’s openness and competitiveness than expected,” it states.

Forecasting the longer-run impacts of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, the research predicts an increase in trade costs of 10.8 per cent for exports to the EU and 11 per cent for imports from the EU, rising to 16.2 per cent and 16.6 per cent respectively, when accounting for likely future EU integration.

As trade barriers look set to increase, the research suggests that regulated and professional services will be hit harder than most during a substantial change to output. However, the new trading relationship with the EU “will not drive a large or swift labour market adjustment” in the UK economy.

“It is more useful to think of Brexit as driving a fall in openness, rather than a big picture sectoral restructuring,” it states.

Regions

In terms of Brexit’s impact on specific regions, the research says that Brexit will increase the existing productivity and income gaps of the UK’s poorest regions, with the real impact of Brexit being a hit to real wages and productivity, exacerbating the long-standing challenges faced by the UK.

“A less-open UK will mean a poorer and less productive one by the end of the decade, with real wages expected to fall by 1.8 per cent… and labour productivity by 1.3 per cent, as a result of the long-run changes to trade under the TCA. This would be equivalent to losing more than a quarter of the last decade’s productivity growth.”

The research concludes that although uncertainty exists over the Brexit impacts to date, especially because of the economic impact of Covid-19, a lasting impact of substantial reduced openness should be expected, alongside widespread productivity and real income shocks.