The state of ill-health

Amidst the growing waiting list crisis in health and social care in Northern Ireland, public inquiries ranging neurology, urology, hyponatremia and potentially care homes have highlighted systemic failings in the health service which go beyond an absence of decision-makers or funding, writes David Whelan.

On Saturday 3 September 2022 a collective of campaigners including those affected by some of Northern Ireland’s worst health scandals gathered at Stormont under the slogan ‘enough is enough’.

The protest served to highlight the extent of recent systemic failures within the health and social care system, on top of the day-to-day pressures which are evident in rising waiting lists and a multitude of missed targets.

The crisis in Northern Ireland’s health system has been long standing and in most cases have been compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic and the stop-start nature of a functioning Executive to implement and fund long-term reform. However, failures extend beyond these existential impacts and when pieced together, the outlook for the current state of healthcare is bleak.

Context

In June, a statutory public inquiry into Northern Ireland’s largest ever patient recall – only converted from an independent inquiry after two years of work – found that the Belfast Trust had failed to intervene quickly enough in the practice of neurologist Michael Watt.

Over 5,000 former patients were invited to have their cases examined for possible misdiagnosis of conditions including stroke, multiple sclerosis (MS), and Parkinson’s disease. The inquiry identified “numerous failings” and said that the failings meant that patterns in the consultant’s work were missed for a decade.

It is estimated that around 20 per cent of those patients who had their case re-examined had not been given an appropriate management plan for their condition and a similar number had not been issued an appropriate prescription.

Alongside a finding that the Belfast Trust should and could have intervened earlier, the inquiry stated that failures were not confined to the Trust and that communications between different organisations and management levels were inadequate.

Worryingly, the findings of patients at the centre of a dysfunctional system which failed to put them first are not unique.

In November 2022, a separate public inquiry established to review the Southern Health and Social Care Trust’s handling of urology services prior to May 2020, is to formally open. More than 1,000 former patients of a now-retired urology consultant were recalled in 2020 following serious concerns about his clinical practice as part of an internal investigation by the Trust.

Added to this, to date over 170 persons have made contact with the Muckamore Abbey Hospital Inquiry announced in 2020 after pressure from families, with evidence gathering now extended until the end of 2022 due to the volume. Muckamore, a hospital for vulnerable adults, was at the centre of abuse and neglect allegations which came to light in 2017 and saw police arrest 34 people, with more than 70 staff suspended. The inquiry will scrutinise the role of the Department of Health, the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority, the Police Service of Northern Ireland and the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, which is in charge of Muckamore Abbey.

Following the publication of a review of leadership and governance at the hospital in 2020, Health Minister Robin Swann MLA apologised for what he described as “a sustained failure of care”.

Also in attendance at the Stormont protest in September were some of the families of five children who died from hyponatraemia in Northern Ireland, a condition which can be caused when fluids are not administered properly. In 2018, one of Northern Ireland’s longest running public inquiries found that four of the five deaths examined had been preventable and its Chair, Mr Justice O’Hara, stating that some witnesses to the inquiry “had to have the truth dragged out of them”, gave a scathing assessment of the health service, saying that “doctors and managers cannot be relied upon to do the right thing at the right time”.

Care homes

Also potentially on the horizon is a public inquiry into the handling of the pandemic in care homes. Northern Ireland’s Commissioner for Older People has called for one after it was revealed that deaths in care homes account for roughly 30 per cent of all Covid-related deaths. The Health Minister has hinted that it is under consideration, but to date nothing has been announced.

Former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced a UK-wide Covid-19 inquiry, which is expected to begin evidence gathering this year, but Scotland has opted to establish its own inquiry. Calling for the Northern Ireland Executive to conduct an inquiry specifically looking at the care and management of residents and care homes, Commissioner Eddie Lynch said: “Covid has impacted us all, but for older people, and particularly care home residents, those impacts have been exceptionally arduous. Over the past year we witnessed the incorrect recording of care home deaths, families having no access to loved ones, personal protective equipment (PPE) supply problems, inappropriate use of do not attempt resuscitation orders, the slow introduction of testing, the transfer of Covid-positive patients into care homes – the list goes on.”

A crisis in waiting

The extent of the systemic failures in health and social care have damaged public confidence in the system, already at a low ebb because of persistent failure to deliver transformation to a system under unsustainable pressure. Despite the delivery of a range of strategies in recent years, the absence of a multiyear Executive budget have often meant that long-term strategies in health have been delivered with the caveat of the need for resources.

In June 2021, Swann announced a new Elective Care Framework to tackle waiting lists to “restore hope” with a planned investment £700 million over five years, however like many of the newly announced strategies, a dysfunctional Northern Ireland Executive and failure of the political parties to agree a multi-annual budget has left plans beyond year one in limbo.

Meanwhile, the health system’s ability to deal with demand is worsening, leading many to assess the state of the current system as broken. Latest hospital figures depict a system that is failing some of the society’s most vulnerable.

Cancer

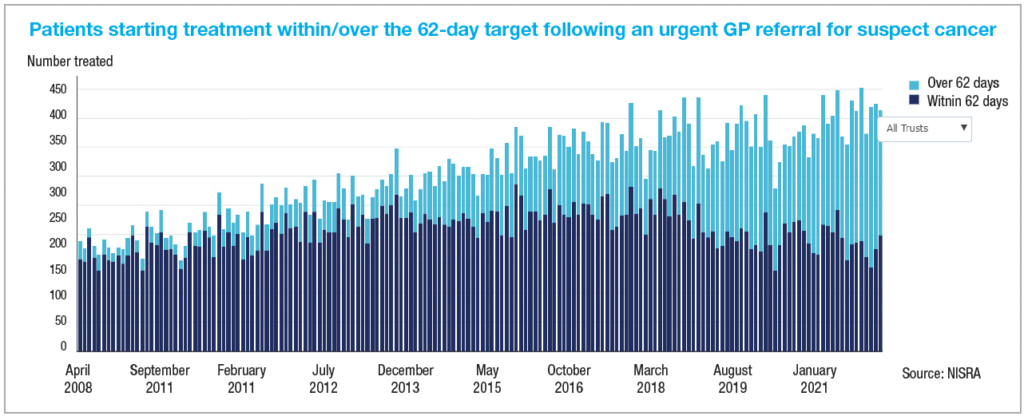

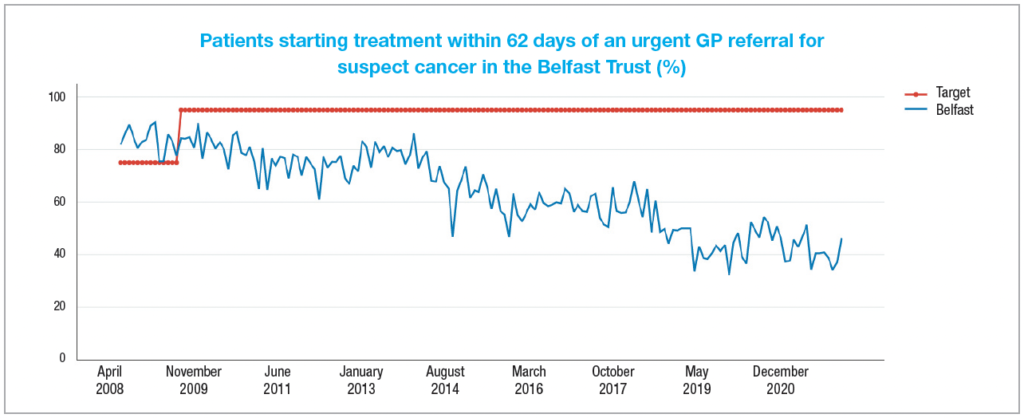

The 2021/22 draft ministerial target for cancer care services states that at least 95 per cent of patients urgently referred with a suspected cancer should begin their first definitive treatment within 62 days. Not only has the target not been met on a regional level for three years, but a significant gap exists between the target and the service being delivered.

In March 2021, just 48 per cent of those urgently referred by their GP with a suspected cancer had begun definitive treatment within 62 days, less than the 49 per cent achieved for the same month in the year previous.

Contextualising the concern around delay, figures collected by NISRA show that over 37 per cent of those patients waiting longer than the 62-day target in March 2022 were diagnosed with urological cancer.

Emergency care

Latest statistics show that almost one in seven emergency department (ED) attendees have been referred by a GP, perhaps reflecting the significant burden also being placed on general practice. Also reflective of the current pressures, almost 7 per cent of ED attendees left before their treatment was complete, a significant jump from the roughly 4 per cent average recorded in 2014.

The Department of Health’s current targets on emergency care waiting times for 2022/23 state that 95 per cent of patients attending type 1, 2, or 3 emergency departments should either be treated, discharged, or admitted within four hours of arrival and that no patient should be waiting longer than 12 hours.

In June 2022, just 51.5 per cent had been seen within the four-hour timeframe across the three categories, a 7.5 per cent fall from the same month in 2021. In the same timeframe, over 2,700 more patients waited over the 12-hour target than had done in 2021, despite EDs experiencing an almost 5 per cent drop in attendances.

Inpatient/outpatient

Outside of EDs the situation is equally bleak, despite a target of 50 per cent of patients waiting no longer than nine weeks for a first outpatient appointment by March 2022, and no patient waiting longer than 52 weeks, over 80 per cent of patients were waiting longer than nine weeks at the end of June 2022 and over half were waiting more than 52 weeks.

The Department’s aim is that no more than 55 per cent of patients should wait longer than 13 weeks for inpatient or day case treatment, with no one waiting longer than 52 weeks, however, at present, the number of patients waiting to be admitted to hospitals has actually risen by over 10 per cent than was the case at the end of June 2021.

Over 80 per cent of patients were waiting to be admitted for treatment longer than the 13-week target and over 58 per cent were waiting over 52 weeks.

Worryingly, diagnostic targets are also being significantly missed. As of March 2022, 75 per cent of patients should be waiting no longer than nine weeks for a test but over 52 per cent were doing so at 31 March 2021. Over a third of patients were waiting more than 26 weeks.

Budget

The prospect of any immediate improvements in service delivery appears minimal when considering that despite political agreement that any future budget would increase resources to the Department of Health to mitigate the crisis, the necessary execution of emergency arrangements around departmental funding in the absence of a fully functioning Executive means no uplift for the Department is available.

In a recent letter to Executive colleagues, Swann said that the absence of an agreed budget would lead to three key funding pressures in the form of staff pay, waiting list pressures and rising energy costs, requiring a potential overspend of some £400 million for the health service to stand still.

Undoubtedly, the failure to secure continuity in the Executive’s decision-making, coupled with the absence of a budget and the additional pressures associated with Covid-19 have hampered health service delivery, however, there is also evidence to suggest that the system as was, was faltering and failing the most vulnerable.

Ambitions to transform the health service must address the shortcomings of frontline care but there must also be recognition that a legacy of systemic failures requires a huge culture change. Only then can public confidence begin to be restored.