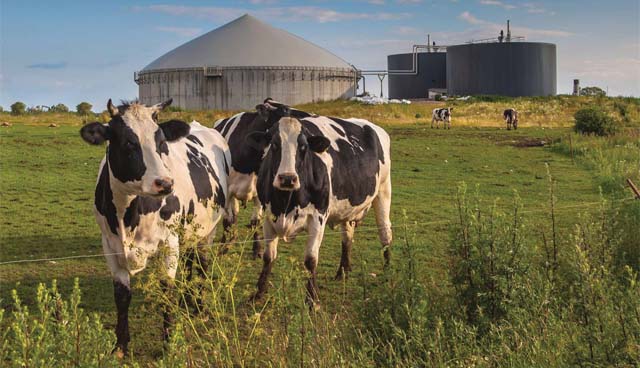

Anaerobic digestion in Northern Ireland

Following the publication of policy options for Northern Ireland’s upcoming Energy Strategy, David Whelan looks at the potential future role of anaerobic digestion (AD) technology and biogases in decarbonisation ambitions.

In autumn 2021, the UK Government will launch a Green Gas support scheme for AD-produced biomethane injected into the gas grid. The scheme, however, will be applicable only in Great Britain.

Despite the uptake of AD technology being significantly greater in Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland has three and a half times as many AD-based generating stations per square kilometre as Great Britain), leading it to be described as the UK’s hotspot for AD, the technologies role in Northern Ireland’s decarbonisation ambitions has yet to be defined.

AD has been recognised as having a role to play in Northern Ireland’s drive towards net zero carbon, especially in a scenario where policy decisionmakers opt for a high gasification approach, whereby biomethane and hydrogen eventually replace natural gas in the grid infrastructure. However, the extent of the role it will play and the supports available to encourage growth will depend largely on the shape the Energy Strategy set to be published by the Department for the Economy later this year.

Anaerobic digestion is a process whereby biomass feedstock is broken down in the absence of oxygen, producing methane and carbon dioxide in the form of biogas. Biogas can be combusted to generate electricity and/or heat (combined heat and power).

Despite a high animal stocking density, meaning Northern Ireland enjoys a wealth of animal waste feedstock in comparison to the rest of the UK, initial uptake of AD technology in Northern Ireland was slow when compared to Great Britain. However, the decision for Northern Ireland not to fast follow Great Britain in closing and subsequently reducing financial support schemes, meant that Northern Ireland became the most attractive region in the UK for AD investment.

Currently, the vast majority of AD facilities in Northern Ireland are farm-based. The UK’s biogas map shows that in June 2019 there were 76 operational AD facilities in Northern Ireland, the majority of which (64) predominantly use agricultural feedstock, with the remaining 12 using municipal, commercial, and industrial waste as feedstock. Out of the 76 AD facilities, 57 use a mix of animal by-products and energy crops and silage to feed their ADs.

The biogas being generated in Northern Ireland is largely used for onsite combined heat and power, however, increasingly, surplus electricity is sold to export suppliers. While undoubtedly the use of biogas for heat and power has a role to play in Northern Ireland’s decarbonisation, most people recognise that its greatest potential impact could be facilitating the injection of upgraded biogas (biomethane) into the existing natural gas grid.

Injection

As well as plans in the UK, other European countries including Germany, France, Italy, and Denmark are already utilising AD-supplied biomethane in their national grids. However, injection of biomethane is currently not being undertaken in Northern Ireland.

A number of challenges stand in the way of the viability of policy that encourages the uptake of biomethane generation technology as a means to decarbonise Northern Ireland’s gas network. The first is the scale of the impact a fully decarbonised gas system (using both biomethane and hydrogen) would have. Currently almost 70 per cent of homes in Northern Ireland and a significant number of businesses still rely in oil for heating. The Utility Regulator estimates that 65 per cent of properties in the region will be connected to the gas grid by 2023 but even if achieved, a significant portion could still rely on fossil fuel for heat, unless an electrified solution is found.

A second challenge is the potential push towards electrification for heat, which could reduce the need for future expansion of the gas grid. The Department for the Economy, in preparation for its Energy Strategy is currently reviewing the costs and benefits of biogas and biomethane, seeking to identify the potential scale or local biogas production, commercial viability, potential additional support and wider environmental and sustainability measures needed. However, a recently produced policy options paper spelled out numerous scenarios for consideration.

The Department has recognised that Northern Ireland’s substantial rural agriculture base can support the growth of biogas and that Northern Ireland’s modern gas network is more suitable for zero carbon gas than older networks, however, it states that in a scenario whereby high electrification is targeted (100 per cent RES-E by 2050), heat pumps provide the majority of heat supplied in the domestic and services sector, complimented by high levels of energy efficiency.

“The Department has set out its recognition that Northern Ireland’s substantial rural agriculture base can support the growth of biogas and that Northern Ireland’s modern gas network is more suitable for zero carbon gas than older networks.”

Such a scenario would negate the expansion of the current gas network and locally produced biogas and hydrogen would aid the network in playing a small role supplementing heat pumps.

However, this is not the case in a high gasification scenario, whereby a greater focus on gas means the network is fully decarbonised with a mix of hydrogen and biogas and is expanded to reach a larger percentage of the population.

The UK advisory body, the Climate Change Committee on assessing the role of biomethane in Northern Ireland described it as a “low-regret option” and recommends continued government support.

Further challenges to AD technology in Northern Ireland exist in the form of public opposition. Although mainly aimed at larger AD facilities, public opposition has been raised in relation to environmental, noise and odour concerns for potential projects in the likes of Omagh, Newtownabbey and Belfast.

Wider concerns have been raised around the environmental impact of incentivising the uptake of AD generation particularly in relation to ammonia. Emissions from ammonia, a source of nitrogen, are increased when large amounts of silage and some litters are stored on site or spread, and nitrogen can cause damage to ecosystems and waterways.

As a result of its agricultural sector, Northern Ireland already produces the UK’s highest ammonia emissions (12 per cent) of any region despite having only 3 per cent of the population and 6 per cent of the UK land area.

Greater roll out of AD technology could negate the need for Northern Ireland to export large amounts of its animal waste, as is the case currently. The Republic of Ireland is Northern Ireland’s main export market for excess animal waste and concern has been raised that while the Northern Ireland Protocol enables this export channel to remain open, any cessation of the Protocol would present a challenge in how to manage excess waste. Higher levels of AD technology reduce the amount of waste that needs to be exported.

AD technology has a greater role to play in Northern Ireland’s energy mix than is currently the case, however, two factors will largely define to what extent it is scaled up across Northern Ireland. The first is what supports are made available through policy and this is likely to be defined through the publication of the energy strategy. The second is the extent to which gas grid injection of biomethane is facilitated.