The cost of the shift

Co-director of the Nevin Economic Research Institute, Paul Mac Flynn, outlines the ongoing shifts in the economy, some of which are being masked by pandemic support.

The story of the labour market over the past year is undoubtedly still centred on the extraordinary government support that has been supplied to firms over the pandemic. With so much effort being expended to try and maintain and preserve the pre-pandemic economy, it is easy to miss the changes and shifts that are already taking place.

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) was a novel development in UK economic policy making, not just because of the scale of support it provided but because of the way it provided it. A furlough scheme keeps people in employment, even if they have no work. In terms of labour market statistics, the furloughed employee is considered to be ‘in a job’ but not ‘at work’. Such a distinction is more than just pedantry.

In Dublin, the approach to supporting workers was quite different. There was a wage subsidy scheme for people working reduced hours, but for those with no work, they were offered the Pandemic Unemployment Payment (PUP). For most workers, the CJRS would be more generous than the equivalent PUP payment, but one of the main benefits of the CJRS is that it maintains the connection between employee and employer.

The objective of the CJRS is therefore not only to provide income protection for affected workers, but also to ensure that when restrictions ease, these same workers can move seamlessly back into work. Of course, the reality is far more complex. While many workers will hopefully move back into their pre-pandemic working patterns, for many the pandemic has fundamentally altered their jobs. Either their employer is no longer operating or their employer is operating in a way which significantly alters the nature or future of their job.

It is too early to know how successful the CJRS has been in preserving the pre-pandemic labour market. Data over the coming weeks and months will give an indication of the medium-term outlook. But looking to the data that we have already shows that substantial change may already be underway.

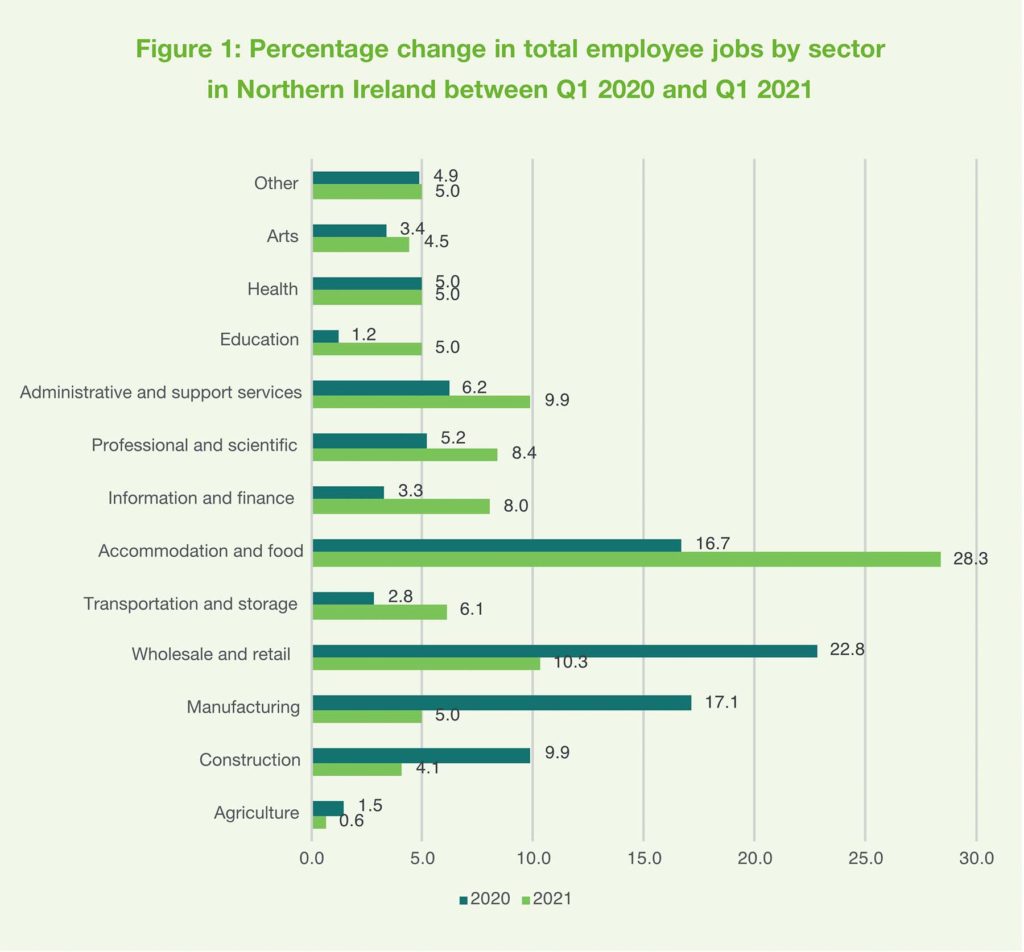

We now have data available for the first quarter of 2021 which can be compared with the first quarter of 2020 as the pre-pandemic benchmark. During that 1-year period there was a net loss of just over 7,000 jobs or 1 per cent of all jobs in the economy. Within that net figure there were over 15,000 jobs lost and just under 8,000 created. To put those figures into context, in the year between the first quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020, there was a net gain of just under 4,000 jobs. Just under 10,000 jobs were created and 5,000 jobs lost.

“We hear much talk of the benefits of flexible working for home life and the environment, but we have to accept that such an enormous change in the way we work is likely to have a significant negative effect on a section of our workforce.”

Compared with the previous year, the scale of job losses experienced between 2020 and 2021 could be seen as a failure of the Government’s labour market policy. However, when you take into account the scale of the disruption that the economy experienced, government policy actually did well to stem the loss of jobs to the extent that it did.

What the job loss figures for the last year can do is give us some idea of the prospects for jobs over the coming months. The sectors where we have seen job loss over the last year do not come as a surprise. As Figure 1 shows, accommodation and food has lost 10 per cent of jobs since last year. These are jobs lost in spite of government support, where the loss of trade could not be stemmed by grants or loans. The arts sector has lost over 8 per cent while wholesale and retail just under 5 per cent.

These three sectors also have the greatest take-up of the CJRS and so it is not surprising that they account for 85 per cent of jobs lost in the last year. There is hope that as public health restrictions continue to be unwound, some of these losses can be made back up as firms begin to expand again or as new firms step in to replace those that have ceased trading. However, such optimism may not hold across the rest of the labour market.

To investigate this, it is worthwhile to look at another sector of employment, administration and support services. We haven’t heard as much about this sector, but it could be an important bellwether in the coming months. This sector not only includes people who work in offices but also people who work in the service of offices. It includes security services, cleaning services and facilities management. It also includes conference and event organisers along with travel agents and office temping agencies.

Administration and support services has lost just under 1,000 jobs in the last year. This can seem small compared to the loss of over 5,000 jobs in accommodation and food. However, administration is a big sector of employment in Northern Ireland accounting for 7 per cent of all jobs compared to accommodation and food which accounts for 6 per cent. It was also a significant job creator in the years following the financial crash accounting for 12 per cent of all new jobs created between 2013 and 2019 compared to 11 per cent for accommodation and food. As a sector it is as important as accommodation and food in terms of both its size and its ability to generate swift employment growth.

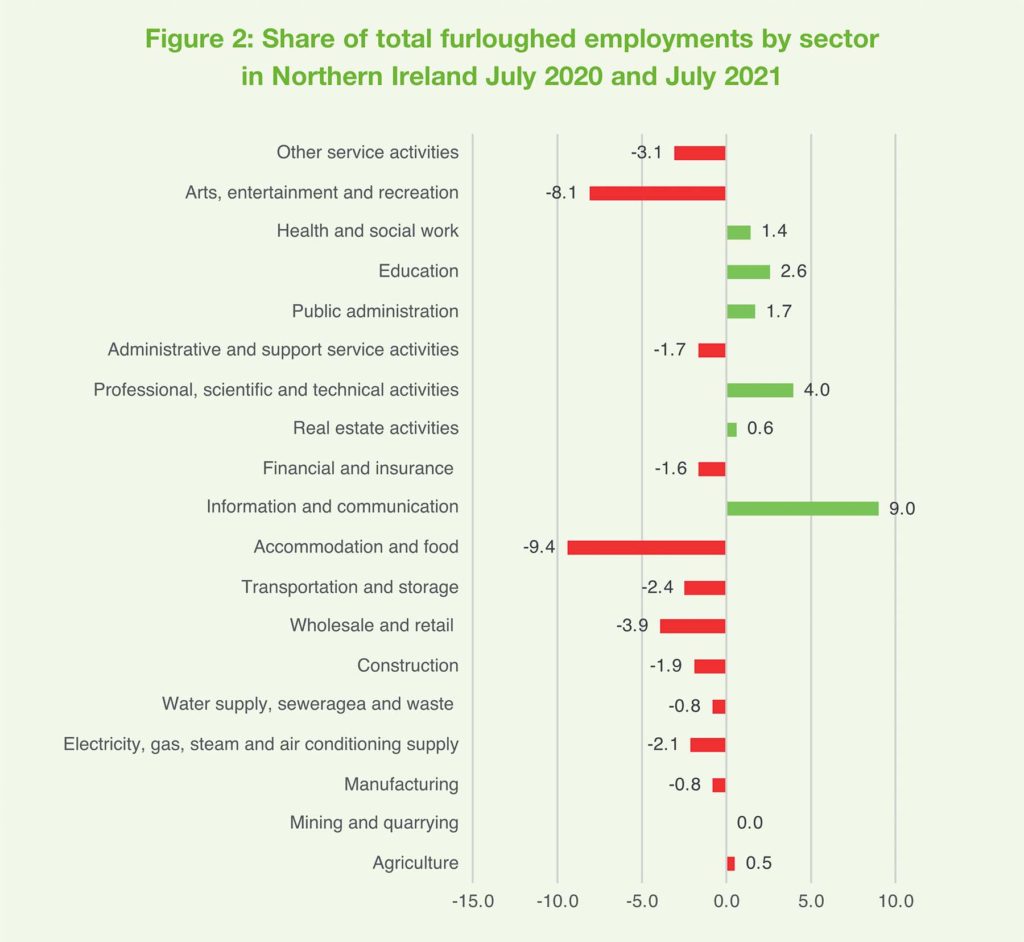

There are reasons to be worried about the prospects for the administration sector. Looking at the progress of the CJRS over the past year Figure 2 shows the sectoral make up of all furloughed employments in July 2020 and July 2021. Accommodation and food stands out as being the largest share of total furlough in both years and has increased its share substantially over the year. However, the administration sector has also increased its share of total furloughed employments and it now sits only just behind the retail sector.

While the road back for hospitality and other sectors looks simple enough, the path of the administration sector is an awful lot less clear. As public health restrictions are lifted, many hospitality businesses can reopen and take staff back on. For the administration sector, the lifting of restrictions may not be enough.

Many, if not most, office workers have been working from home since last March under government advice. Even when this restriction is lifted, it is not clear how many people will return to the office some, or even all of the time. We hear much talk of the benefits of flexible working for home life and the environment, but we have to accept that such an enormous change in the way we work is likely to have a significant negative effect on a section of our workforce.

The CJRS may help hospitality businesses return to pre-pandemic employment, but the same cannot be said for the administration sector. The move toward flexible working may be a positive one but there needs to be acceptance of the cost of this shift in terms of jobs. The CJRS may help many return to employment but we will also need a new financial commitment to those who cannot return to employment.