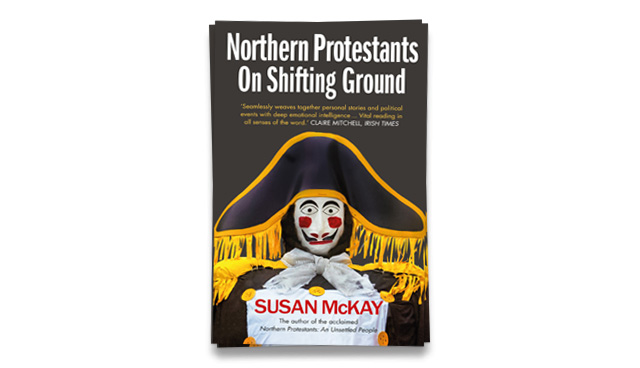

Northern Protestants: On Shifting Ground

Journalist and author of Northern Protestants: On Shifting Ground, Susan McKay, discusses an evident shift away from the “ethnic huddle” associated with unionism in Northern Ireland.

A coach who has known young Rhys McClenaghan from the start of his career was on the radio talking about the remarkable speech the 22-year-old Newtownards athlete made immediately after a small error in his gymnastic routine denied him the chance to win a medal for Ireland at the Olympics.

McClenaghan acknowledged his disappointment but did not dwell on it. Instead, he spoke of his pride at having competed as an Olympian. He was still at the beginning of his career, he would be back “a more dangerous man”, he promised.

The coach said he was an inspiration to other young people. She mentioned his talent, his skill, and his dedication. But the special quality that enabled him to accept his defeat so gracefully was, she implied, his self-confidence. It was, she commented, a rare enough quality in Northern Ireland. She is right.

Instead, there is a lot of militancy, which is the opposite.

When working on my new book Northern Protestants: On Shifting Ground, however, I met many people who are passionate about encouraging the young to think for themselves and to work with others, whatever their background, for the common good. I never liked the concept of the ‘Protestant/unionist/loyalist’ community, with its wretched PUL acronym.

It is worth considering why the other bit of that matching set, the ‘Catholic/nationalist/republican’ or CNR community, failed to take hold. Perhaps the need for an ethnic huddle is felt more keenly within unionism. This is certainly true for political unionism, which is a fundamentally defensive politics. ‘What we have we hold’. ‘Not an inch’. ‘When the Ulsterman’s back is against the wall, he’ll come out fighting’. ‘No surrender’.

As young DUP councillor Dale Pankhurst put it to me, “it’s the paranoia in the psyche”. He was speaking in the context of a young Catholic woman and her children having been intimidated out of moving into a house they had been allocated in Tyndale, in north Belfast. People might have thought, he reasoned, what if such a person is “a real hard-line republican?” Trojan horses come in many cunning disguises. The DUP has resorted to its traditional route of drumming up electoral support, instilling fear that the other side is otherwise going to come and take away everything you hold dear: Your home, your identity, your flags, and your culture.

Pankhurst described “a spectrum of grievances”. The PUL community now felt that the Good Friday Agreement was geared against it, he told me.

That is an accurate summation of the DUP’s position. But within the broad range of people from a Protestant background, there is actually far more diversity, far more fluidity, far more ease when it comes to identity.

“There’s a whole lot more to life than just sticking with your own,” Danielle McDowell told me. She is a women’s development officer for the IFA and Ulster University, and head of women’s and girls’ football at Crusaders.

She also has 47 international caps for Northern Ireland and has been known since childhood as “the wee footballer.” She talked to me about how important sport is in building confidence and physical and mental resilience among girls.

Youth worker Amy Johnson gave me a shocking glimpse into quite how important this is when she talked about the girls she works with in Monkstown Boxing Club out in the big working class housing estate in north Belfast. “You can see the potential in them but a lot of them are just at rock bottom, no self-esteem, no self-confidence, no aspirations,” she said. “We have had young people that have wanted plastic surgery to change their facial features at age 15. Just heart-breaking.”

Amy said that whereas girls turn inward when their confidence is low, boys are inclined to lash out. Her colleague, Daryl Clarke, who is a boxing champion as well as a youth worker, talked about his hometown, Carrickfergus. He came from an area that had a heavy paramilitary presence and a lot of drink, drugs, and anti-social behaviour. He said some of the boys he went to school with are trapped in self-destructive patterns of behaviour established when they were teenagers. They were stuck in a rut. For some, it ends in suicide. “Young men have had these barriers up for so long and the stigma around not talking about their feelings, thoughts and emotions is crazy.”

The club counters bad influences with good ones. World champion boxer Carl Frampton is a regular visitor to the club. I had heard him speak at an anti-sectarianism rally when there was rioting across the peace line in Tigers Bay in north Belfast. Frampton said he came from Tigers Bay and had rioted himself as a boy. “People have been stirring the pot again, and young people are being manipulated,” he said. “It just made me overwhelmingly sad.”

Youth work has demonstrably great outcomes — and is underfunded. Millions are poured into the so far failed project of trying to get loyalist paramilitaries to “leave the stage”. Early in 2021 the DUP’s leading figures met with a hitherto scarcely known group called the Loyalist Communities Council. It was set up primarily as a kind of ‘old boys club’ for paramilitaries by one of Tony Blair’s advisors. These old boys duly began to thump the old drums, soon claiming that a fierce younger generation of fighters for God and Ulster were coming behind them. But they were not. The younger paramilitary generation is now pure gangster. Sectarianism is a side-line, keeping Catholics, and “ethnics” out of the flaggy zones.

Young women, in particular, find little sustenance in this toxic fare. One of the people I interviewed was teenager Rebecca Crockett, who had just finished school in Derry. “I wasn’t even alive in a time when there wasn’t a Good Friday Agreement,” she said. She did not even think about whether her friends were Catholics or Protestants. “It doesn’t come into your head,” she said. What mattered was loyalty to people. Her politics were global. “Brexit and the rise of Trump have made our generation more politically aware,” she said. “And it has led to movements like the climate movement….and the anti-gun campaign in America and the March for our Lives.”

Ashleigh Topley became a campaigning feminist when she found out that the DUP for which her family had always voted as a matter of tradition, was vehemently determined to prevent women from having an abortion in Northern Ireland, even in circumstances like those she found herself in, carrying a baby with a fatal foetal abnormality. Ashleigh and others got the law changed, but unionists are still trying to block its implementation.

Young people, and many older people, see no reason for alarm if there is a Catholic majority, as there may well be when the census results come in next year. If there is a border poll and it turns out a majority want a united Ireland, they’ll go with that, even if it wasn’t what they voted for themselves. They have the confidence to participate in democratic processes. They have resilience.

Kenny McFarland, chair of the Londonderry Bands Forum, grew up during the Troubles and is determined that the peace must be kept. “Our leaders have taught us working class people that we need to know our place, and it is at the bottom,” he said. “We still struggle to break that, and it leaves our community at a massive disadvantage.” He spoke for many when he said simply: “We want normal politics.”

Susan McKay’s book Northern Protestants: On Shifting Ground is published by Blackstaff, which has also just re-issued her 2000 book Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People. Susan writes for the New York Times, the Guardian, the London Review of Books and the Irish Times. She is currently writing a book about borders for which she received an Arts Council of Northern Ireland major individual award.