New Decade, New Approach

The New Decade, New Approach agreement outlined a series of priorities and ambitions for a reformed Executive and Assembly, however many of the details were purposefully ambiguous. Now operational, the institutions are under pressure to deliver changes in the two years remaining of the current mandate, writes David Whelan.

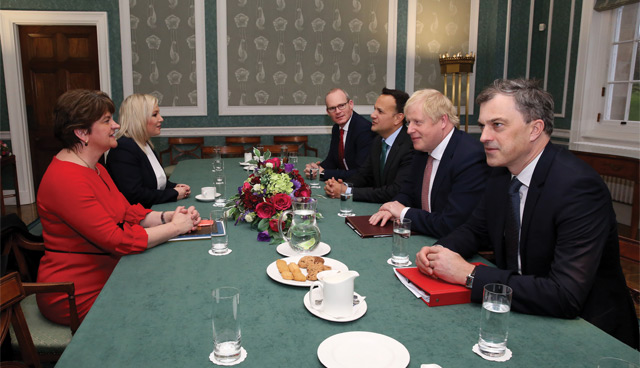

Three years of Assembly absence were ended after details of a draft deal published by the UK’s now former Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Julian Smith and Ireland’s Foreign Affairs Minister Simon Coveney effectively bounced parties into a decision to reconvene the Assembly and restore the Executive.

While Northern Ireland’s main parties have emphasised their involvement in sculpting the deal’s detail, throughout the numerous previously unsuccessful attempts to restore power-sharing, the actual joining together of these various arrangements in a draft deal effectively forced parties to take or leave the offer on the table.

In the end, public pressure and the lure of enhanced, but unspecified, Westminster finance was enough for parties to compromise on their previously held red lines and form an Executive. Remarkably, no hard figures were outlined in terms of enhanced funding prior to the deal being signed.

New Decade, New Approach is a comprehensive document which promises significant changes and investment in almost every sector across Northern Ireland. However, questions have lingered from the very beginning about the feasibility of and, ambiguity around some of the objectives included. For example, reducing hospital waiting lists and resolving the industrial disputes with public sector workers were obvious priorities. In these instances, additional resources have provided at least a pathway to resolution. However, on the other hand, commitments to “support educating children and young people of different backgrounds together” or “develop a regionally-balanced economy with opportunities for all” lack details on the process or financial arrangements for achievement.

Financing the ambitions of the deal is a source of contention going forward. Northern Ireland is in line for a significant uplift in its Barnett consequential as a result of the UK’s increased spend on public infrastructure outlined in March’s Budget.

This alone will not be enough to cover the various objectives within the deal. Resolving Northern Ireland’s waiting list crisis was costed at close to £1 billion by the Permanent Secretary of health in 2019. Water and wastewater infrastructure across Northern Ireland, an enabler of economic development, needs over £3 billion of investment over the next seven years.

A factsheet produced by the Department of Finance indicated early proposals indicated a £2 billion package, only £760 million of which it deemed as “new funding”.

Finance Minister Conor Murphy used his first Ministerial statement to call on both governments to deliver on the financial package promised.

Pointedly, he said: “The New Decade, New Approach document presented by the governments contains ambitious commitments for public services and workers. To deliver these commitments, the Governments pledged a substantial injection of funding, over and above the block grant.”

Identified needs: Health and education

Health and education took primacy in the new deal with both the British and Irish Governments recognising the wider desire to resolve the current challenges. Alongside the pledge to immediately settle the ongoing pay dispute in the health sector, the deal outlined a desire for the Executive to introduce an action plan on waiting times. However, its only firm guarantee in this regard is for those waiting over a year for outpatient or inpatient assessment/treatment at 30 September 2019 to be off the waiting list by March 2021.

Delivering the reforms outlined in the Bengoa report, something initiated by the previous Executive, is also acknowledged by the deal but little detail is associated with the ambition. Some hard targets do exist. The delivery of 900 extra nursing and midwifery undergraduate places over three years, for example, and the delivery of mental health and cancer strategies by December 2020. The coverage of an extra 100,000 patients by multi-disciplinary teams in general practice by March 2021 builds on an initial investment made through the confidence and supply agreement funding. However, the provision for a graduate entry medical school at the Magee campus of Ulster University was a commitment made by the previous Executive.

Noticeably, there is a shift in language when the deal turns to the teachers’ industrial dispute in education when compared to health. Where the deal pledges to “immediately” resolve the dispute in health, in education the dispute will be “urgently” resolved.

Also to be funded is a commitment to ensure every school has “a sustainable core budget”. Last year the combined overspend of Northern Ireland’s schools was £22 million, however, bridging this gap alone will unlikely solve the current crisis with many schools warning that they are being forced to undertake extraordinary measures in order to reduce their expenditure.

Again, beyond these core commitments, the deal is void of precise detail in regard to the education sector. Education has long been a divisive issue between the Assembly’s two largest parties with clear differences in their policy priorities for future delivery. In this context, the pledge to review of education provision including a focus on “the prospects of moving towards a single education system”, appears optimistic at best. Given the recognised increased pressure on schools in supporting young people with special needs, promise of a new special educational needs framework will be welcomed. However, some criticism has been levelled at the decision not to include a delivery date.

Culture and identity

Comparisons can be drawn between the current deal and the draft deal which emerged after the collapse of talks in February 2018. Then, the major sticking point was around the provisions for an Irish language Act. Since then, parties have developed further their desire to see the Petition of Concern reformed, with some stating their inability to re-enter an Executive without clear progress.

Compromise is evident on all sides in relation to detail surrounding rights, language and identity. Sinn Féin’s red line of a stand alone Irish Language Act (ILA) has been crossed. Instead the main components of an envisaged ILA are incorporated into a wider package which also includes provision for a similar commissioner for Ulster Scots/Ulster British tradition in Northern Ireland.

Concerns have been raised about the future form of an envisaged Office of Identity and Cultural Expression. As Ireland approaches the centenary of partition, the marking of which will undoubtedly be contentious, the office’s place within an Executive Office-sponsored framework “recognising and celebrating Northern Ireland’s diversity of identities and culture and accommodating cultural difference”, appears overly optimistic and potentially divisive. The office will provide the central point for the principals of encouraging and promoting “reconciliation, tolerance and meaningful dialogue” between national and cultural identities in Northern Ireland. Critics have suggested that history dictates that such a role could invariably be bogged down with dealing with complaints.

Strategy

The deal has set out an ambitious list of planned strategies that it will hope to bring forward in the short-to-long term. Success of these strategies will depend on a shift away from the template which has created a raft of previous weightless strategies. Northern Ireland has a legacy of creating strategies which lack hard targets, clearly defined pathways and outcome accountability. The quality of the planned strategies to be brought forward by the Executive must have clearly defined and meaningful outcomes if they are to affect change.

Planned strategies:

- Anti-poverty strategy;

- Economic/Industrial Strategy;

- Investment Strategy;

- Energy Strategy;

- Racial Equality Strategy;

- Disability Strategy;

- Gender Strategy;

- Sexual Orientation Strategy;

- Active Ageing Strategy;

- Children and Young People’s Strategy;

- Childcare Strategy;

- Child Poverty Strategy;

- Irish Language Strategy; and

- Ulster Scots Strategy

Irish language campaigners have acknowledged significant progress in the intention to appoint an Irish Language Commissioner, the facilitation of interaction between Irish language speakers and public bodies and a draft Irish language strategy within six months. However, limitations of such an appointment have also been recognised. For instance, the commissioner, will be agreed by The Executive Office (TEO), effectively offering each of the two largest parties a veto on any appointment. TEO will also be required to agree the best practice standards for the use of the Irish language by public authorities to be developed by the commissioner.

In terms of powers, the commissioner will lack almost any powers of enforcement. For example, when appointed, a commissioner will “investigate complaints where a public authority has failed to have due regard to those standards”. The remit of the commissioner appears to be centred on research and recommendation rather than direct action in addressing need for change.

Devoid of almost any detail in the deal is the provision to establish the ‘Castlereagh Foundation’, a fund which will “support academic research through universities and other partners to explore identity and the shifting patterns of social identity in Northern Ireland”. Reading between the lines, such a fund appears to fall in behind a unionist push to create a civic voice for Britishness through research and educational material. The volume of funding and subsequent allocation with regard to this fund must to be scrutinised given the level of ambiguity about its creation and purpose.

Citizenship

Also embedded in the deal is a rule change by the UK Government around how people in Northern Ireland can bring their family members to the UK. The change was prompted by the well-publicised case taken by Emma de Souza based on citizenship and the right to identify as an Irish citizen without having to renounce an unacknowledged British citizenship. The law change relates directly to de Souza in that she can now apply for UK immigration status for her husband on broadly the same terms as the family members of Irish citizens in the UK. However, while the change should rectify the de Souzas’ personal case and cases similar to that, it fails to address the wider citizenship issues highlighted by the case.

The UK Government has not legislated for the implementations of the birth right provisions within the Good Friday Agreement within UK domestic law. This means that questions remain as to what further rights restrictions for those identifying as Irish citizens in Northern Ireland, a key tenet of the Good Friday Agreement, will exist when Brexit takes place.

Petition of Concern

The reform of the Petition of Concern (PoC) falls short of what had been envisaged by most parties, particularly the Alliance Party, the SDLP and the UUP. However, the pledge of “meaningful” reform to return the PoC back to its original was sufficient to allow the parties to return to the Executive. The mechanisms of the original petition remain largely intact, however, it will now require the backing of more than one party to trigger it. In this instance, independents will be classed as such, reducing the difficulty of achieving wider support. Delay has also been introduced, undoubtedly to ensure parties take greater consideration when utilising the mechanism. The PoC will only apply after the second stage of both Executive and Private Member’s Bills and each successful use would trigger a 14-day period of consideration. There is no outline for consultation requirements or political discussion within this time frame, raising questions as to the effectiveness of such a measure.

Reform

Upon the appointment of the Assembly committees, concerns were raised that little recognition of necessary structural reforms of the institutions identified in their absence were being considered in the delivery of a fresh term. One of the most obvious in this regard, is an over-reliance on the block grant in the delivery of public services. The absence of a link between taxation and expenditure has previously led to a lack of responsibility for the implications of spending. Another is the level of scrutiny and accountability within the Executive’s departments. All but five MLAs are not members of parties within the new Executive and, as a result, all the new Chairs and deputy Chairs of both the standing and statutory committees originate from a party within the Executive. In essence, the greatest mechanisms for holding the Executive to account will be chaired by associates of that same Executive.

Infrastructure

Many regionally significant planning decisions were awaiting Infrastructure Minister Nichola Mallon in her early days in office. Many of the projects name-checked in the deal are unfulfilled from previous executives and agreements. What is new is the Irish Government’s pledge of €110 million over the next three years for infrastructure funding.

Projects listed in the deal include:

- York Street Interchange;

- wastewater infrastructure;

- a Belfast to Dublin connectivity strategy;

- Narrow Water Bridge;

- the medical school in Derry; and

- Casement Park.

Changing how devolved government works has been a long-identified necessity if the institutions are to have a sustainable future. The deal sets out a number of priorities in this regard, undoubtedly hoping to avoid the trappings of the past that have led to the institutions collapsing. One of the key changes outlined is a direct prevention of what occurred three years ago through the resignation of Martin McGuinness and the immediate halt this brought to work in the Executive and the Assembly. Again, the Irish and British Governments appear to be utilising delay as a tool to finding a solution to any future disputes. To this end, the deal extends the period to 24 weeks the period before an Assembly election must be called in the event of a breakdown of the institutions. Importantly, it stipulates the retention of ministers in office in a “caretaker capacity” during this period, in an attempt to avoid the abrupt end of decision-making powers which occurred in 2017.

Pre-empting the findings of the delayed report into the findings if the Renewable Heat Incentive Inquiry published in March, the deal outlines the need for the immediate production and implementation of the ministerial, civil service and special advisor codes. As it stands, there is no legal deterrent on the parties and officials to return to the ways of working which facilitated a series costly blunders and the eventual collapse.

Brexit

Despite dominating the headlines in the absence of the institutions, Brexit occupies minimal space within the 62-page deal. In what would undoubtedly have been a useful instrument as the UK negotiated the shape of its withdrawal in the last two years, both internally and externally, the Executive has established a Brexit sub-committee, chaired by the First and deputy First Minister and inclusive of each party on the Executive. Questions had been raised as to whether such a committee would have been able to coherently lobby for Northern Ireland’s interests given the parties’ divergent Brexit policies, however, with the UK likely to secure its exit and the beginning of a transitional period at the end of January, a cohesive position within Northern Ireland is now more plausible and could ensure a unified front as the UK and EU negotiate their future trading relationship.

Environment and energy

With regard to energy policy, the deal simply gives emphasis to a direction of travel already well-established in Northern Ireland. A future energy strategy with a goal of net zero carbon is already being developed. However, the deal does set out a defined direction of travel in terms of developing environmental priorities. The deal says the Executive “should” bring forward a Climate Change Act (contrasting language from other priorities which use “will”) and establish an independent Environmental Protection Agency. Neither of these have been included in the Executive’s legislative programme.

The absence of any discussion around greater all-island collaboration in this area is noticeable, especially given a commitment to enhance connectivity and infrastructure between north and south. The document also makes no reference to the North South Interconnector, long identified as necessary to ensure security of electricity supply in Northern Ireland and undoubtedly a priority for new Infrastructure Minister Nichola Mallon.

In analysing the future sustainability of Northern Ireland’s political institutions, much will depend on the availability of resources to implement change. New Decade, New Approach is so broad that it is unfeasible to expect rapid change in all areas, however, change will be necessary in key sectors such as health and education in order to retain public confidence.

Away from the priorities, the Assembly and the Executive will be required to outline detailed action plans and benchmarked progress in many areas where detail is scarce. Necessary reform of the institutions should be prioritised to avoid a reoccurrence of the collapse. In the midst of planned economic expansion, Brexit must still be a vital consideration given its potential detrimental impact on growth aspirations.