General election: Northern Ireland

For the first time in its history Northern Ireland has elected a nationalist majority to Westminster but a decisive Conservative majority means that neither nationalists nor unionists will hold much sway over future government policy.

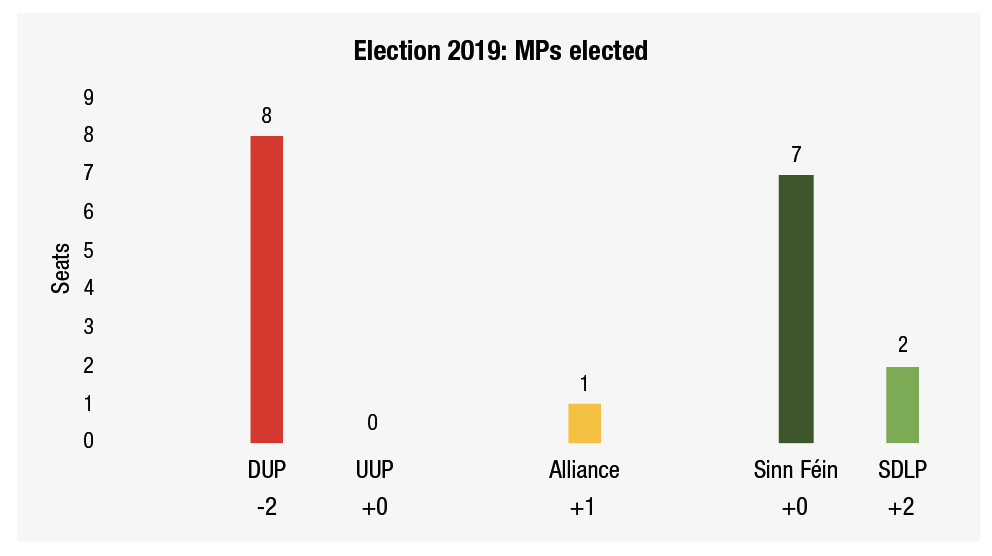

While still remaining as the holders of the largest number of Northern Ireland’s seats at Westminster, December’s general election results represented a major blow for the DUP. Losing two of its 10 previously held seats, the party also lost its influence over Boris Johnson’s government. A gain of 47 seats for the Conservatives mean that it will no longer rely on the DUP for a house majority, ending the confidence and supply agreement.

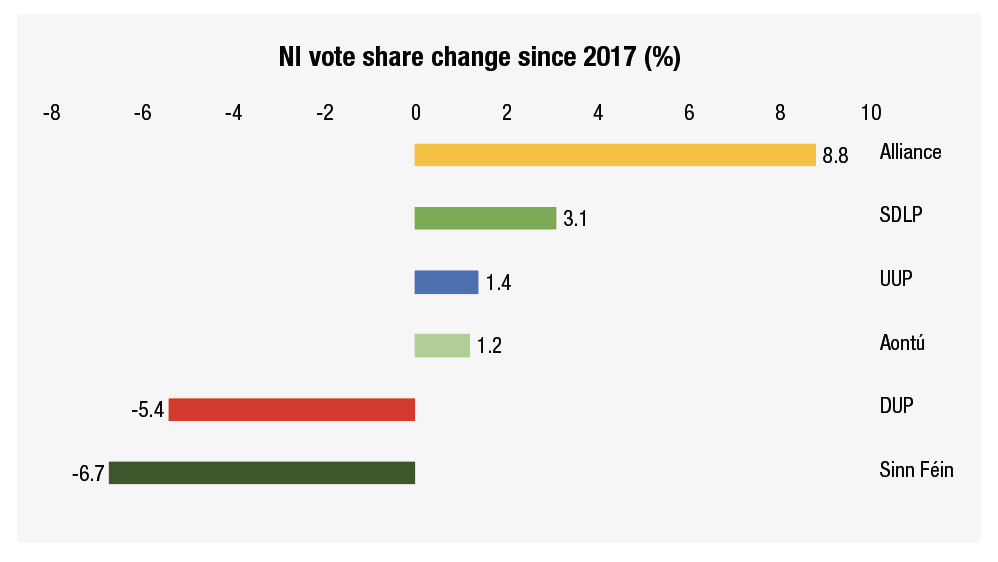

However, the DUP alone were not the only party to take a hit from the electorate on polling day. They may have dropped the most seats but the party’s vote share decrease of 5.4 per cent was still smaller than that felt by Sinn Féin who dropped their vote by 6.7 per cent overall. Sinn Féin’s victory in North Belfast, with John Finucane unseating the DUP’s deputy leader in Nigel Dodds, has allowed the party to deflect somewhat its vote decline but it has struggled to cover up the significance of the unseating of its own MP in Foyle, Elisha McCallion, by a re-energised SDLP.

The scale of SDLP leader Colum Eastwood’s victory in Foyle was unexpected, taking 17,000 votes more than the sitting MP and a vote share of almost treble that of Sinn Féin’s. It was a similar story in South Belfast where, aided by an electoral pact which saw Sinn Féin and the Green Party not contest the seat, Claire Hanna was expected to run sitting MP the DUP’s Emma Little-Pengelly, close. Instead she won comfortably, overturning the previously held DUP majority of almost 2,000 votes to win by more than 15,000.

While the SDLP can claim the success story of the night in raising their representation in Westminster from zero to two, the Alliance Party have also been able to claim election success. The party elected just one MP in the shape of deputy leader Stephen Farry but took 17 per cent of the overall 803,367 votes cast in Northern Ireland. Farry’s victory was emphatic given that the seat had been earmarked by the DUP as a potential seat gain, even before the announced retirement of sitting unionist independent MP Sylvia Hermon. The party also took solace from a number of strong performances in traditional unionist heartland seats, most notably, Sorcha Eastwood’s ability to slash the majority held by MP Jeffrey Donaldson by some 13,000 votes.

Elsewhere seats remained largely the same. The DUP’s Carla Lockhart was able to comfortably retain the seat of her departing colleague David Simpson in a contest with Sinn Féin’s John O’Dowd. Michelle Gildernew also retained the Fermanagh and South Tyrone seat for Sinn Féin, despite a unionist electoral pact, but only by 57 votes.

UK

The sheer scale of the Conservative Party win (365 seats to Labour’s 203) spelt the end of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. Labour’s drop of 59 seats means that his reign was untenable and that Boris Johnson should now be equipped with the support to push ahead with his “oven ready” Brexit deal and his timeline of exiting the EU by the end of January.

The ending of the unionist majority in the House of Commons will have little impact on Conservative Party policy, however, alongside the election success of the Scottish National Party, debate has been sparked about the future of the UK’s union.

Scotland’s largest party gained 13 seats, meaning it now holds 48 of the 59 seats on offer in the country. In a landslide victory, the party took 45 per cent of the vote in Scotland, a vote share increase of over 8 per cent since 2017 and in doing so took seats from the Conservatives, Labour and unseated Liberal Democrats leader Jo Swinson.

Prior to the election, Sturgeon had pledged to send a letter to the new Prime Minister before Christmas requesting a second referendum on Scottish independence. Johnson has refused to back calls for a referendum, a position Sturgeon has labelled as unsustainable.

Brexit has undoubtedly energised Scottish nationalism and attempts to stay within the EU through breaking links with the union. The same argument could be made for Northern Ireland. The pro-remain vote was mobilised in many constituencies across the region and while not all would be advocates of reunification, the topic is now firmly on the table.

Significant is the fact that Belfast, the capital city of the region sculpted by unionism, now has three nationalist MPs to one unionist MP. This is a complete reversal from 2017.

The likely implementation of an Irish Sea border will be damaging for unionism. The DUP, as unionism’s main voice, opposed the sea border but they back Brexit and they backed Boris Johnson until it was too late. The border will create a significant barrier between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom and is therefore perceived as a threat to the future of the United Kingdom too.

Saddled with the rise of English nationalism, Scottish nationalists and Northern Irish nationalists now hold the largest number of seats representing their region. It will be increasingly difficult for the Government to ignore this fact.