Northern Ireland economy 2019

Positive employment and output figures for the Northern Ireland economy have given cause for cautious optimism but don’t fully mask the fact that Northern Ireland continues to suffer from a much slower rate of recovery than the UK and faces imminent disruption from Brexit.

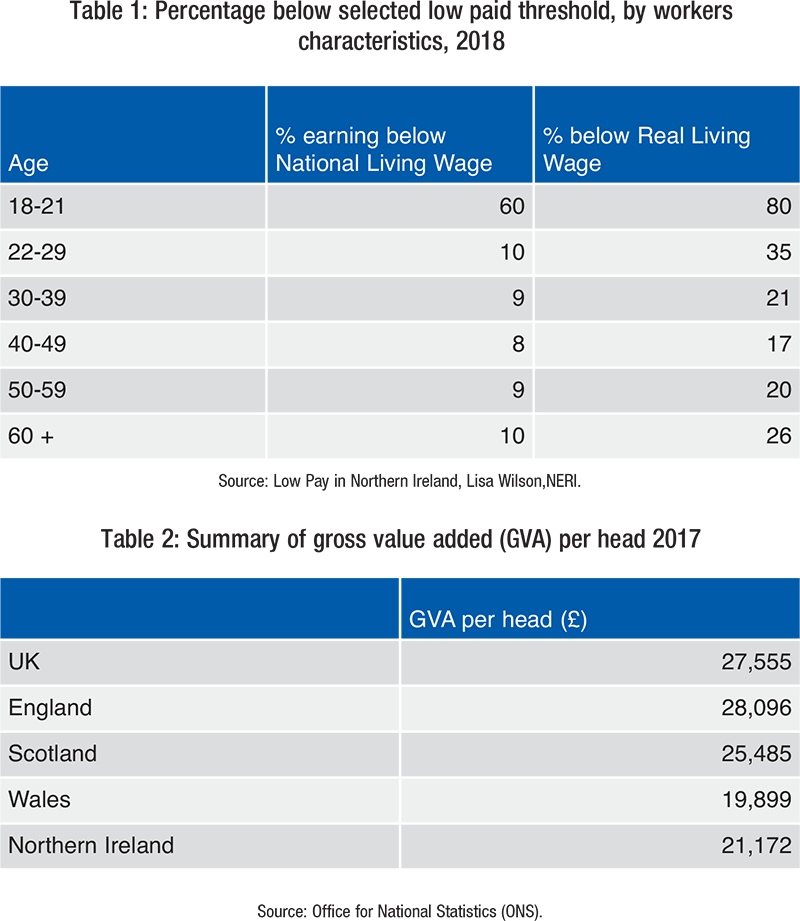

Northern Ireland’s labour market continues to show positive trends with the employment rate (Figure 1) reaching a near record high of 72 per cent in 2019. This is coupled with a record low unemployment rate which decreased to 2.8 per cent, significantly below the unemployment rate of the UK (3.8 per cent), Republic of Ireland (4.6 per cent) and the EU (6.3 per cent).

The inactivity rate in Northern Ireland fell by over 1 per cent to 25.8 per cent and while all broad sectors experienced job increases the majority of these new jobs were accounted for in the services sector (73 per cent).

The Northern Ireland labour market improvements follow the general trend of the UK, where employment is at its highest ever, however while the unemployment rate is comparatively low, Northern Ireland has the second lowest employment rate of all the regions and the highest inactivity rate.

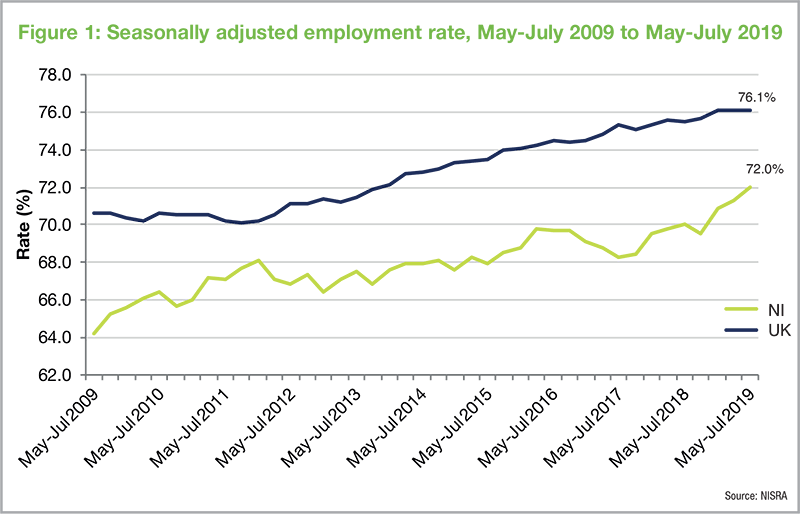

Added to this is the fact that Northern Ireland’s labour market suffers from a prominent feature of low pay (Table 1), which has a direct impact on consumer expenditure, something Northern Ireland’s economy is over-reliant on to support economic growth.

In 2018, 28 per cent of workers in Northern Ireland earned less than the real living wage. The majority of these workers tended to be in the services sector, the largest sector for job growth this year.

At the same time, Northern Ireland suffers from a productivity problem when compared to the UK, which is a major impediment on an economy’s ability to significantly grow (Table 2). Since 2009, the annual average growth rate in the UK has been around 1.2 per cent compared to just over 0.1 per cent for Northern Ireland.

Output

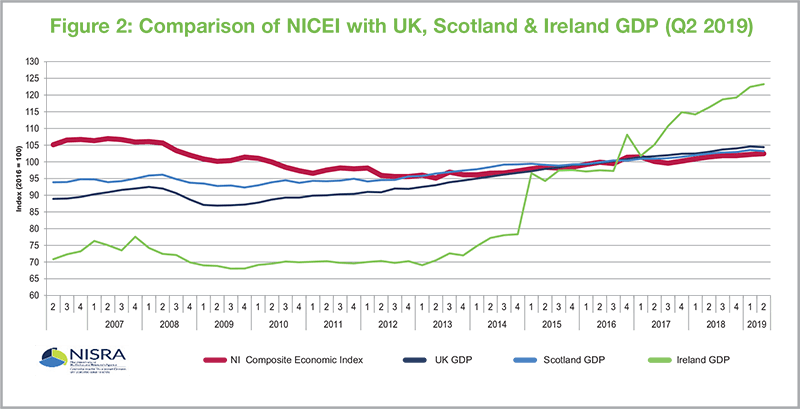

Services output has grown by 0.5 per cent over the year and is the highest it has been in a decade, although it is still some 2.6 per cent lower than a high point in 2006. The sector’s growth was a key factor in a real term economic output increase of 1 per cent over the year, slower than the UK rate (1.3 per cent), according to the NI Composite Economic Index NICEI (Figure 2).

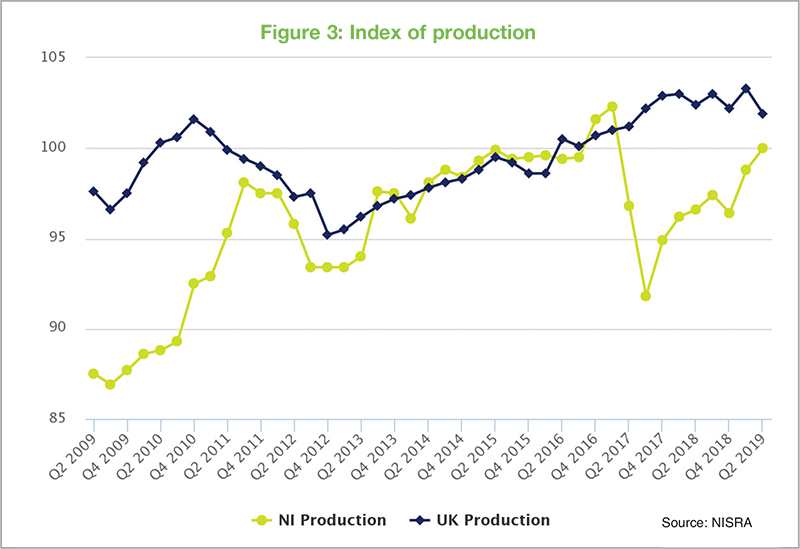

NISRA’s Index of Production (IoP) for Northern Ireland, which provides information on the output of the production industries, manufacturing industries and market trends, is up by 3.6 per cent over the year but saw a decrease in output of 0.5 per cent (Figure 3).

Often seen as a key sector for measuring economic performance, most recent statistics show a 1.5 per cent decrease in the total volume of construction output but marked an upward trend since the end of 2013. Quarterly analysis showed a steep decrease in repair and maintenance work (6 per cent) and new work (2.8 per cent).

Trade

The most recent statistics on trade analyse the sales and export statistics for the year 2017 and therefore do not factor in the growing uncertainty around Brexit and the implications of any potential trade barriers.

Purchases by companies in Northern Ireland rose by 3.2 per cent to £1.4 billion, driven by a 16.3 per cent annual rise in services purchases. Imports were up 8.3 per cent. Imports from Ireland rose by 14.6 per cent to £2.6 billion and imports from the rest of the EU were up 5.2 per cent to £2.2 billion. Imports from the rest of the world were up 5 per cent to £2.3 billion and purchases from Great Britain increased by 6.1 per cent to £13.3 billion.

The value of goods exports was £9.15 billon, an increase of 6.8 per cent over the year and the largest markets for Northern Ireland exports were the EU (£5.4 billon), with £3.2 billion of that to the Republic of Ireland.

It is estimated that around 6 per cent of all external selling businesses in Northern Ireland sold goods and services to all four external markets, and some 5 per cent of businesses purchased goods from these markets, highlighting Northern Ireland’s businesses’ reliance on trade across multiple markets. How Brexit will have an impact on this remains to be seen but recently published evidence by the Department for the Economy outlined that a no deal outcome would lead to a major reduction in Northern Ireland’s exports to Ireland by at least 11 per cent, raising to 19 per cent if non-tariff barriers are included.

The report also outlined a potential 9.1 per cent fall in GVA and a 6 per cent decline in FDI, as well as other unmeasurable impacts such as declining business competitiveness, limitations on business growth and on consumer spending. A no deal exit would be catastrophic for the future of the Northern Ireland economy.

In attempting to establish the current impact of Brexit uncertainty on the Northern Ireland economy, Ulster Bank’s latest Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) highlighted a six month decline of business activity, a seven month decline of new export orders and an eight month decline in employment.

Returning to the labour market and it is clear that a hard Brexit would detrimentally impact Northern Ireland’s most vulnerable sectors such as agri-food, manufacturing and haulage, potentially costing up to 40,000 jobs and the future of some industries.

Brexit will likely further exacerbate predictable challenges in the labour market. An imminent likely slow down in employment growth, coupled with continuing low levels of productivity are usually diagnosed as improvable through increased exposure to export markets and the attraction of migrant labour and skills, both of which could be impeded post-Brexit.

Another factor coming down the tracks is a slowdown in consumer spending. While Brexit could have an untold impact in this area, current data is pointing to a possible slowdown even without its impact. The Ulster University Economic Policy Centre’s Summer 2019 Report states that the current UK household’s savings ratio of 4.5 per cent represents a sustained low longer than records stretching back to 1963. The statistic suggests the potential for weaker consumer spending growth in the medium term. Northern Ireland’s discretionary weekly income is just over half of the UK average and as the Northern Ireland economy is so dependent on consumer spending for growth, any similar decline would have a significant impact.

However, some optimism lies in the unknown. If proposals to keep Northern Ireland both aligned to the UK and within the EU customs union come to fruition, there is a potential for Northern Ireland to become a big draw for FDI. Quite what economic impact this would have relies on the nature of the future relationships between both the UK and the EU and globally.

Additionally, a planned, significant increase in level of expenditure on public services, following a decade of cuts, recently announced in the UK Government’s 2019 Spending Review will have a Barnett consequential for Northern Ireland which in turn has the potential to promote or sustain supply-chain related jobs.