Additive manufacturing: the third industrial revolution

Manufacturing is experiencing a revolution from the inside. A design-driven approach is gaining traction, thanks to the ever-evolving technology of 3D printing and additive manufacturing. agendaNi reports on the latest industrial innovation set to transform industry in Northern Ireland and beyond.

Many of the benefits of additive manufacturing can be found at the point when conventional methods of manufacturing reach their limitations. The process allows for highly complex, intricate structures which still offer a significantly lighter weight, without compromising on the strength of its foundations: 3D-printed products are stronger, more stable products than their manually created, traditionally manufactured counterparts. In a Northern Irish context, the development of additive manufacturing may offer much-needed solutions to the workforce, skills and resourcing challenges facing the sector.

Recent years have seen the process of additive manufacturing and 3D printing gain global prominence. Where only five years ago the idea would have been beyond comprehension, the technology has been commercialised, and most importantly, domesticated: 3D printing devices are now available for household use, with broad applications – and even broader gaps in regulation. Indeed, homemade creations of those who own their own printers demonstrate just how far this nascent technology has come. Gone are the days when additive manufacturing was an expensive and time-consuming process, reserved for the best-equipped factories: beginners can now effectively ‘print’ designs and essential parts using the technology.

Roots of revolution

Whilst the technology continues to establish itself in a household setting, its applications to industry have long been understood. The earliest additive manufacturing equipment, along with its materials, were being developed as early as the 1980s. Hideo Kodama of Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute pioneered the concept in 1981 when he invented two additive methods for fabricating 3D plastic models with photo-hardening thermoset polymer. The technology conceived by the manufacturing visionary has retained the same core process since its inception, where the ‘UV area’ is controlled by a mask pattern or scanning fibre transmitter. Decades later, Kodama’s brainchild in 3D printing has become a synonym for additive manufacturing, both in Northern Ireland and further afield in Europe and the USA.

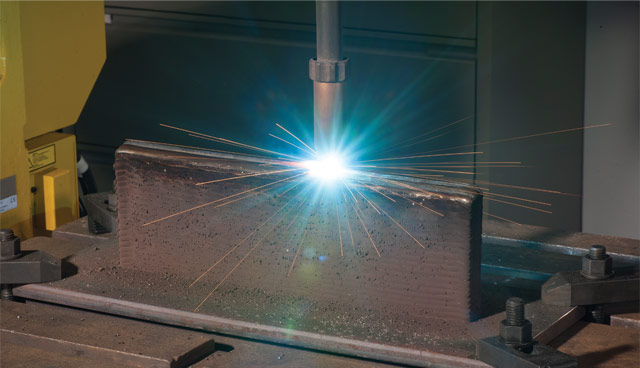

Successive years have seen continued developments in additive manufacturing. A patent for the stereolithography process was submitted in 1984, before its eventual overtaking by fused disposition modelling in 1988. Selective laser melting was championed in 1994, laying the foundations for modern 3D printing as we recognise it today. In 2019, developments in the technology have culminated in a universal recognition that additive manufacturing could enhance sustainable development in the developing world. Indeed, the possibilities of the technology appear to be endless: printed, stable and secure homes have been proposed for use in third world countries, in what represents a new method of construction which nearly eliminates plastic waste — a major blight on Ireland’s coasts and waters.

The historic inevitability of human error, according to advocates of the technology, will be eliminated. The meticulous nature of computer-aided design (CAD), along with its cousins in 3D scanning and photogrammetry software, ensure that errors are significantly reduced. Beyond the reduction of error, additive manufacturing’s pre-emptive qualities have been highlighted as a game-changer in the sector: designs can be ‘piloted’ and corrected before final print, allowing verification in the design of the object before it is printed. Similarly, the manufacturing method has been highlighted for its intuitive modelling process for geometric data, which works similarly to plastic-based arts such as sculpting.

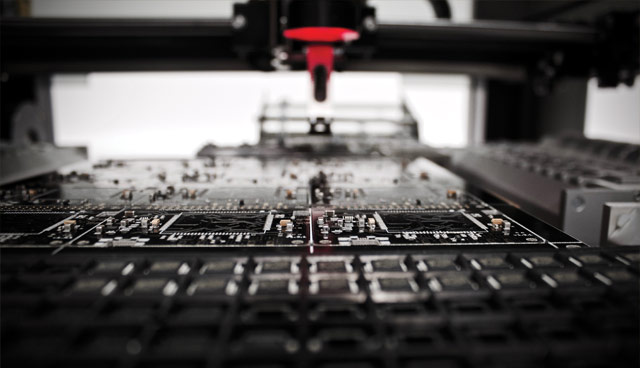

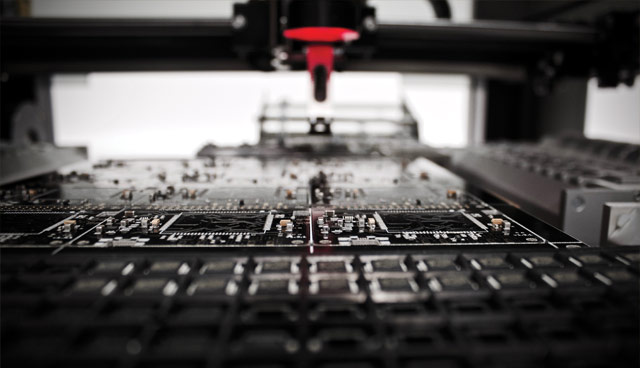

Despite the similarities that lie at the core of the technology, additive manufacturing is not to be confused with conventional methods of material removal. Manufacturing history has traditionally seen workpieces effectively carved and milled from a solid block. Additive manufacturing, however, builds up a series of components in layers. Whilst many of the materials are similar to those seen in traditional manufacturing methods, a definitive feature is applied to all materials that go through the additive process: they are all available in powder form. Indeed, the range of powdered materials continues to grow in correlation with the development of additive manufacturing, to the point in 2019 where a range of metals, plastics and composite materials are available.

Rapid prototyping

Whilst 3D printing has found strong application in building parts, tools, houses and even medical devices, the technology has found itself particularly relevant in the field of rapid prototyping. Rapid prototyping, the construction of illustrative and functional prototypes, is now being facilitated by additive manufacturing in series production. This effectively allows Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) across all sections of industry the opportunity to establish a unique profile for themselves, fundamentally based on its benefits to the customer, its potential to save significant costs and its environmentally-positive nature — allowing for greater chances to achieve sustainability goals.

Overarching all of the benefits of additive manufacturing is its allowance of ultimate freedom to the designer. Functional features are easily and expertly optimised and integrated, and the manufacturing of products in small batches is made more affordable, with lowered unit costs and new levels of product customisation previously unseen in serial production. Considering this, along with the fact that Northern Ireland’s manufacturing sector has grown almost three times faster than the rest of the UK, highlights the region as a potential future bastion of advanced manufacturing.

Despite the technology’s spearheading by its Chinese and American pioneers, Ireland is emerging as a hotspot for additive manufacturing and 3D printing facilities. Northern Ireland has responded to the emergence of 3D printing by moving its major facilities and activities up the value chain, allowing it to become an effective hub for global manufacturing firms. Indeed, the region may avail of the breadth of experience granted by companies long-established in Ireland, including Seagate, Wrightbus, Denroy and Bombardier. Beyond the extensive cache of manufacturing expertise to exploit, prospective firms considering Northern Ireland as a future base may now look towards the country as a European leader in logistics planning.

Often referred to as ‘the third industrial revolution’, additive manufacturing is also demanding more from higher education, and Irish universities are meeting that challenge with fresh courses and new approaches to learning, including cold spray applications, enhanced boiling heat transfer coatings and metal-additive manufacturing. As the technology evolves, Northern Ireland could establish itself as a future European knowledge capital of advanced manufacturing, with diverse experience which encompasses aerospace and defence, construction, materials handling, consumer products and more. Indeed, the region’s world-class reputation for its work with polymers may help it flourish in a new industry which places the molecular material at the core of its offering.