Summer 2018 economic analysis

‘Some good news, but challenging times ahead,’ writes Gareth Hetherington, Director of the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre, an independent economic research unit based in the Ulster University Business School.

The local economic indicators have been pointing in two opposite directions over the last six to 12 months. Job creation has continued apace and unemployment is at record lows, but economic output, as measured by GVA (Gross Value Added) appears to have stalled. This points to the broader problem of lower productivity as job numbers have fallen in high productivity sectors (such as the financial services sector) and we have witnessed strong job growth in lower productivity sectors (such as social care and hospitality).

This local economic performance is set against a relatively strong global growth picture, where both the UK and Northern Ireland economies have benefitted from increased global trade through higher exports. Setting aside trade war tensions and other geo-political risks, continued expansion in export markets is essential to support continued economic growth locally.

Returning to the labour market, even if businesses continue to create job opportunities, the low levels of unemployment will make it increasingly difficult for employers to fill vacancies. Closing this shortfall in labour can be solved by raising inward migration and attracting the economically inactive back into the labour market. However, both these solutions have their problems, Northern Ireland has struggled to attract high numbers of overseas workers following the devaluation of Sterling and the economically inactive tend to have lower skills making them less suitable for the job opportunities available.

Therefore, if economic output is to continue to grow, productivity growth will have to increase (i.e. we raise the economic output per worker), typically through increased business investment and automation. In the long-term productivity growth is the only sustainable way to increase standards of living and support higher real wages.

Brexit: is a ‘no deal’ really likely?

Brexit continues to dominate the headlines as does the political brinkmanship both within the UK and between the UK and the EU. The talk of preparations for a ‘no deal’ must be recognised in the context of the current phase of negotiations and both sides are waiting for the other to blink. A ‘no deal’ is not in any party’s interest and therefore an agreement must still remain the most likely outcome, but reaching a deal may not be that easy.

The UK Government has been unwilling to make substantial preparations for a ‘no deal’ and therefore that threat at this late stage lacks credibility. At the time of writing, the chances of the EU accepting the ‘Chequers deal’ appear to be in the balance, but even if both sides fail to reach agreement by October, a ‘no deal’ is still not inevitable and perhaps even unlikely.

In a scenario where the Government has reached the end of its negotiations without a deal, MPs are likely to assert their authority. The majority of members across all the major parties were ‘remain’ supporters and therefore it seems inconceivable that they would simply sit on their hands for five months and let the UK leave the EU in March 2019 without a deal. Although defying the referendum result and reversing Brexit is highly unlikely, it is more plausible that a cross-party majority would coalesce around a soft-Brexit, perhaps with the UK remaining in the customs union. This would be a highly unusual move, but we are in highly unusual times.

Migrant labour in Northern Ireland

One of the few areas of agreement relating to Brexit, is the recognition that immigration played a key role in the referendum result. But understanding the role of migrants in the economy is critical to informing any post-Brexit immigration policy. Foreign born workers made up 10.2 per cent of the overall labour market in Northern Ireland in 2016 compared to just 4.7 per cent in 2004. Therefore migrant labour is playing an increasingly important role in the local economy.

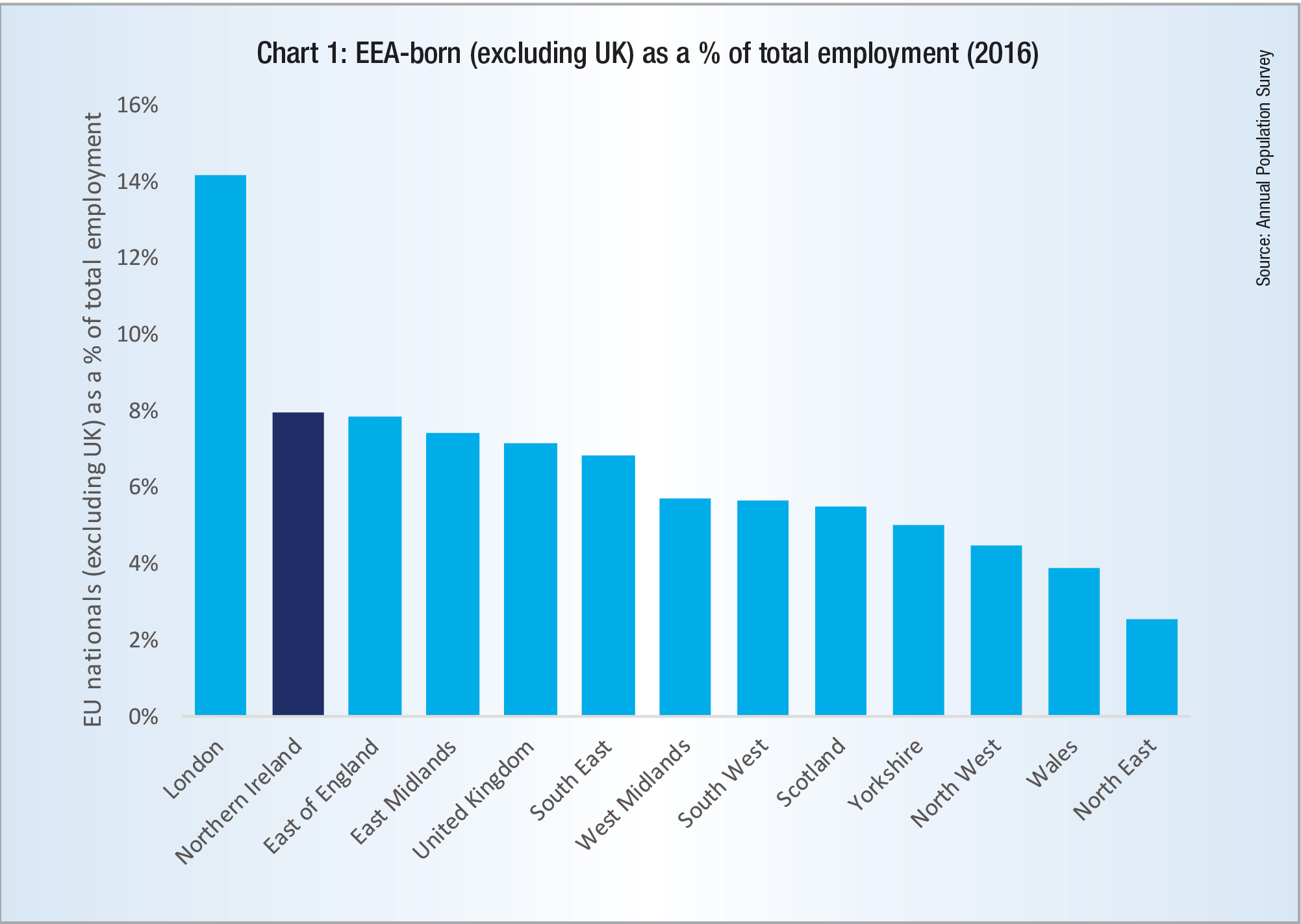

Northern Ireland is very reliant on the European Economic Area (EEA) as a source of labour. EEA born workers represent 8 per cent of total employment in Northern Ireland, ranking second only to London across all UK regions (see Chart 1). Northern Ireland therefore has much more limited experience in sourcing labour from regions where there are currently no freedom of movement rules.

Migrants taking most of the new jobs created

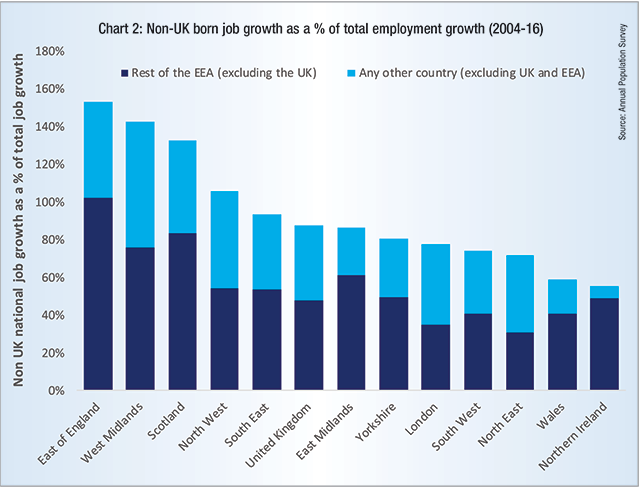

Foreign-born workers accounted for most (55 per cent or 50,000 jobs) of all employment growth in Northern Ireland over the 2004-2016 time period. Whilst that is a significant percentage, it was the lowest proportion across all 12 UK regions (see Chart 2). In other regions of the UK such as East of England and the West Midlands, there has been a fall in the number of ‘local’ workers and migrants have therefore filled all the additional jobs created. Migrants have therefore had a very important role in the employment growth story across the UK and it is clear why employers are so keen for freedom of movement of labour to continue, particularly with unemployment at such low levels.

Migrants taking the jobs locals do not want

Migrants also seem to be taking the jobs that Northern Ireland workers do not want. Approximately 83 per cent of the increase in ‘low skilled’1 jobs, between 2004 and 2016, were taken by migrant labour, compared to only 13 per cent of the increase in ‘high-skilled’2 employment over the same period.

If future UK migration policy reduces the supply of overseas workers, local firms will need to consider other options. This may include attracting more local workers, possibly through higher wages, but given unemployment is currently at very low levels, encouraging the ‘harder to reach’ economically inactive groups back into employment may be needed.

Another option is to consider increased automation to reduce the need for labour. As most migrant jobs are lower skilled, these roles may be easier to replace with capital than higher skilled roles.

The impact of automation

The replacement of workers (labour) with machines (capital), is often viewed in very binary terms, it is either potentially catastrophic with fears of increased unemployment or it is the route to sustained economic productivity growth. Employees are naturally concerned about losing their jobs, but similarly, automation holds out the potential for higher quality goods and services and generates new jobs in the development and operation of those new technologies.

Historical perspectives

Fears about automation are not new. In 1821, the economist David Ricardo argued that technological progress would create mass unemployment and in the 1930’s Keynes forecast that technological progress would increase living standards and that the reduced demand for labour would require employees to work for only 15 hours per week. Ironically, Keynes’s main concern was how society would fill the additional leisure time.

With the benefit of hindsight, these concerns were misplaced. The new technologies created jobs in new industries and have significantly increased standards of living, (but alas not reduced the working week to 15 hours).

The impact on the Northern Ireland economy – jobs impacted does not mean jobs lost

A review of previous research shows a range of estimates in terms of the number of jobs impacted. Encouragingly, the research also suggests that automation is likely to create at least as many jobs as are lost.

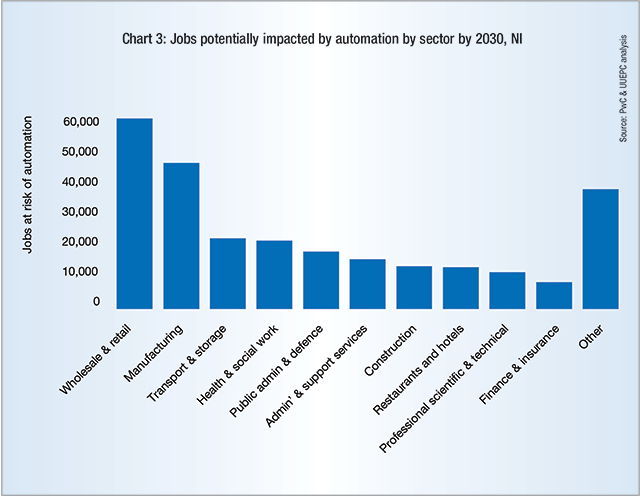

Based on UK research, the UUEPC, in partnership with Catalyst Inc, published research on the impact of automation in Northern Ireland. This reflected the specific composition of the local labour market and found that sectors such as retail, manufacturing and logistics (transport and storage) are likely to be impacted most (see Chart 3).

Importantly, jobs impacted does not necessarily mean jobs lost. Individual tasks associated with a specific job could be automated rather than the entire job itself being replaced. Typically, this should provide the employee with more time for higher value added activities.

Mass unemployment is therefore highly unlikely, which holds true from a historic perspective. There has been huge technological progress since the time of David Ricardo, but there has never been more people working in the UK than there is today. Moreover, the UK has to attract people from overseas to fill the job vacancies the economy is creating.

Policy implications

At the macro level, automation has been good for society but at the micro level it can cause significant challenges for some groups. As a result an education and skills framework is needed which prepares young people for the future skills needs of the economy but also upskills those in employment as their job roles evolve.

In addition, consideration should be given to identifying the skills profile of the human resource that will become available as a result of automation and appropriate ways to make use of that resource identified.

The UUEPC is currently planning to undertake further research into the impact of automation in Northern Ireland which should published in early 2019.

Buoyant jobs market, weak output performance

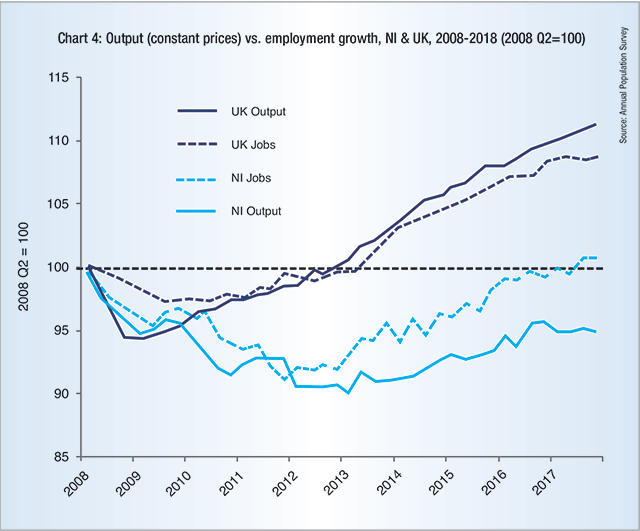

The profile of the jobs and output recoveries between the UK and Northern Ireland economies have been somewhat different. The UK experienced a relatively subdued recession with total jobs falling by 3 per cent and output by 5 per cent over the two year period from 2008 to 2010. Northern Ireland, in contrast, experienced a more prolonged recession, lasting almost five years with a 10 per cent loss in its workforce and a similar contraction in economic output (chart 4).

Fast forward a decade from the start of the financial crisis and the UK economy has recovered reasonably well with employment levels and output significantly higher than their pre-recession levels. Northern Ireland on the other hand has only recently passed pre-recession levels of employment but output still remains 5 per cent lower than in 2008. This success in job creation is welcome but limited output growth suggests the job rich recovery has been in lower productivity sectors.

Lower productivity in Northern Ireland

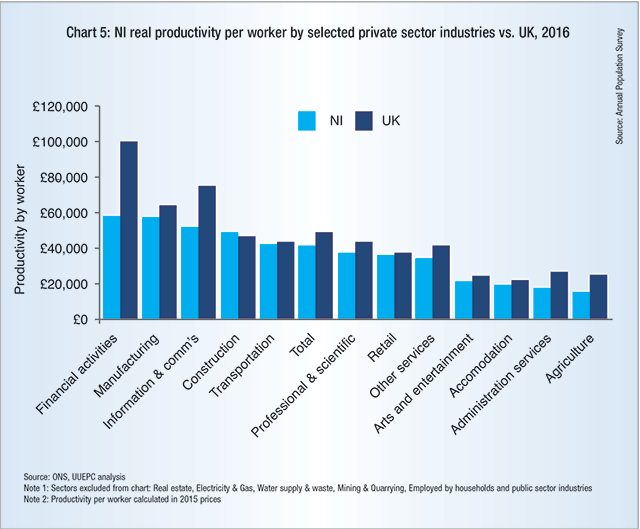

In general, Northern Ireland workers produce lower levels of economic output than equivalent UK workers in the same sector (Chart 5). Typically, sectors operating in internationally competitive markets (i.e. exporters) have higher levels of productivity. In the UK, this includes sectors such as Financial Activities, Information & Communications and Manufacturing, however, in Northern Ireland, Manufacturing is the only predominant export sector and achieves a productivity level similar to that in the UK. In contrast, sectors such as Financial Activities and Information and Communications in Northern Ireland predominantly service the local market and as a consequence have much lower levels of productivity. It should be noted that this is changing, with some high profile service sector exporters, but there is still a way to go.

Ongoing productivity problems are not unique to Northern Ireland. The UK has also experienced a slowdown in productivity performance relative to its G7 peer group. Understanding the reasons for weak productivity performance has been a key challenge for economists and policy makers in recent years. The UUEPC is conducting research into Northern Ireland’s productivity challenges alongside the recent labour market expansion in typically low productivity sectors. This research will be published in early autumn.

The Outlook

The Bank of England took the much anticipated step of increasing interest rates to 0.75 per cent at its recent August Monetary Policy Committee meeting. The ‘old normal’ level of interest rates was around 5 per cent, however, in this post-financial crisis world the ‘new normal’ would seem closer to 1.5 per cent. The UK seems to be treading a middle path between interest rates in the US and the EU. The current Federal Funds Rate (i.e. US base rates) is 2 per cent, with further increases anticipated in 2018 and 2019. In contrast, the Euro Area Interest Rate is 0 per cent and the European Central Bank has signalled that rates are unlikely to change before September 2019.

The Bank of England’s objective for some time has been to ‘normalise’ rates which in turn would allow them to reduce rates sufficiently to fight the next recession. The challenge the Bank of England (and other Central Banks) have is raising rates without causing the recession they are trying to avoid. In short, interest rates are on the rise but very slowly.

Looking forward economic growth is likely to remain sluggish. There are four broad areas of spending in the economy which collectively have to grow for the economy to grow overall:

- Consumer spending: the economy has been very reliant on consumer spending to support economic growth in recent years but in 2017 UK households became net borrowers (i.e. spending surpassed income) for the first time in 30 years. This is a clear indicator that the consumer is living beyond its means and consumer spending could be in line for a correction;

- Export revenues: global trade has been buoyant and combined with a lower exchange rate, the UK has benefitted from an increase in exports. However, strong export growth needs to continue at a time when threats to global trade are also on the increase;

- Business investment: low levels of business investment has been a recurring economic problem in the UK for many years. Business investment levels held steady in the wake of the Brexit referendum, but economic growth will require increased business investment levels moving forward; and

- Government spending: continued spending restraint since 2010 has helped to bring down the budget deficit quite significantly, although overall public debt remains high. The Chancellor has some scope to increase spending, however this is limited and he will likely want to keep a war chest in the event of a negative fallout from Brexit.

Finally, the economy locally has defied expectations and continued to create jobs, albeit economic output has fallen in Q1 2018. A fair wind will be necessary for job and economic growth to increase into the medium term.

Gareth Hetherington is Director of the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre, an independent economic research unit based in the Ulster University Business School in Jordanstown.