Measuring social enterprise value

Brendan Murtagh and Andrew Grounds of Queen’s University Belfast write in agendaNi about the current value of social enterprise to the Northern Ireland economy.

The global financial crisis and the subsequent rise in unemployment and poverty have renewed attention on the social economy as a policy solution in new austerity politics. Viewing the sector as more than a crisis response or cheap alternative to welfare is a problem for its image; but also how it measures its economic, social and environmental value. Part of the problem of making the case for the social economy is the lack of credible evidence on its value, policy contribution and most of all, impact on underserved communities.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers surveyed 473 social enterprises in 2013 and showed that while there are a small number of large organisations, most were small scale, limited in their capacity, undercapitalised and highly grant reliant.

Last year, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) published a report on ‘Cities, the Social Economy and Inclusive Growth’ and showed that social enterprises had created pathways for employment, well-paid jobs, new services, businesses and facilities, in even the most disadvantaged communities across Belfast. As their report emphasises, the sector fails to properly account for its complex social, financial, community relations and environmental effects. There has been considerable investment in evaluation in community development, the voluntary sector and donor philanthropy, such as the Inspiring Impact Hub, supported by Community Evaluation Northern Ireland. Bryson Charitable Group developed an ambitious Social Value Framework that monitors social economy interventions on stakeholder engagement, inclusion, wellbeing, sustainability, social innovation and capacity for reinvestment. Similarly, Social Return on Investment (SROI) attempts to valorise a range of social, community, policy and financial outcomes to describe the monetised leverage, usually of grant aid. Government funders, donors and social investors share this broader concern for ‘outcomes’ and shifting the emphasis away from measuring activity and programme delivery, to identify the value added of one policy or project choice over another.

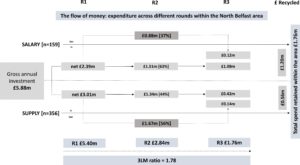

The New Economics Foundation (NEF) sets out a methodology for understanding the impact of social enterprises on the local economy and in particular, the distinctive multiplier effects of different ‘rounds’ of expenditure inside and outside the neighbourhood. The 3LM approach involves; first establishing total net expenditure and for most social enterprises, this falls broadly into suppliers, salaries and charitable investments. The second round examines, in real terms, where the expenditure takes place, either inside or outside the designated area, sectors of the economy, types of enterprises and labour markets. The third round then looks at how much of the individual salary and supplier payments are actually re-spent within the area and how much ‘leaks out’ of the local economy. The aggregated effects of these spending rounds give an overall multiplier ratio and enables money to be traced across place, beneficiary groups, economic sectors, supply chains and so on. By concentrating on actual expenditure, it also provides a more stable measure of regeneration effects as illustrated by two businesses: the Ashton Community Trust (Ashton) in inner-north Belfast; and LEDCOM in Larne.

Ashton employs 160 people mainly in its training, childcare, youthwork and property management business lines and has grown steadily over the last 10 years. In 2015/16, the gross annual expenditure was £5.88 million and, as the diagram shows, this was subdivided between £3.01 million on 356 suppliers and £2.39 million on net salaries. The second round of spending shows that 63 per cent of employees live in north Belfast and 36 per cent of suppliers were based within the parliamentary constituency. Local suppliers re-spend £0.42 million in north Belfast and £0.14 million re-enters the economy from suppliers based outside the area. Similarly, £1.08 million of salaries are spent locally, while some spending (£0.12 million) again re-enters the neighbourhood from people based outside the area. In summary, 30 per cent (£1.76 million) of all net expenditure by Ashton is retained within north Belfast. The total local multiplier effect of cumulative rounds of spending shows that for every £1.00 that is invested by Ashton, an additional 78p is generated in the local north Belfast economy. The analysis also shows that 81 per cent of supplier expenditure and 64 per cent of all salaries were located in the top 20 per cent disadvantaged wards in Northern Ireland. Moreover, 33 per cent of ACT employees earn above the Northern Ireland salary median of £20,200 and most trading is with other social enterprises outside north Belfast. Of the total expenditure of £5.88 million, £4.37 million (74 per cent) is spent within the social economy and £1.98 million (66 per cent) of all supply spending is with other social enterprises. It is worth noting that in 2016/17, turnover has increased to nearly £7 million and more than 200 people are now employed, enabling multiplier effects to be measured across time as well as space.

LEDCOM has a different economic focus by supporting small business development and social enterprise start-ups through technical assistance, facilities and human resource management. The decline of manufacturing has hit east Antrim particularly badly and the search for new indigenous enterprises is now an important strategy for local economic development. LEDCOM has fewer staff (8), supplier base (143) and turnover (£0.75 million) than Ashton, but supports 49 firms in its business parks and these in turn create significant effects on employment, supply chains and emerging business clusters. The 3LM analysis of the core expenditure of LEDCOM shows that 37 per cent is retained within mid and east Antrim and that for every £1 invested by LEDCOM, an additional 87p is generated in the local authority area, when the three-round analysis is calculated. As with Ashton, LEDCOM has created strong interdependencies by trading within the social economy so that of every £1 spent on salaries and suppliers, 53p is spent within the sector.

Ashton and LEDCOM are significant businesses but operate in different and equally challenging economic conditions where private and public markets are increasingly failing. They start businesses, support entrepreneurship, create significant employment and provide pathways to work as well as much needed local services and facilities. They are not the same as private businesses but nor do they displace them, knowledge-led growth strategies or the emphasis on inward investment. Explaining the value of the social economy will be important in creating a better enabling environment for the distinct and multi-layered effects of the sector to grow in partnership with private businesses. The ‘Social Enterprise Northern Ireland’ network makes clear that the sector is not asking for hand-outs or grants but wants to see the type of legislation, investment programmes and social finance to support a diverse, broadly based and fair regional economy.

Brendan Murtagh is a Chartered Town Planner and Reader in the School of Planning Architecture and Civil Engineering at Queens University Belfast.

Andrew Grounds is a Research Assistant in the School of Natural and Built Environment at Queens University Belfast