Climate ambition

At this year’s Energy Ireland conference the International Energy Agency’s incoming Executive Director Fatih Birol gave a keynote address detailing how the energy sector will have a key role to play in combating climate change.

At this year’s Energy Ireland conference the International Energy Agency’s incoming Executive Director Fatih Birol gave a keynote address detailing how the energy sector will have a key role to play in combating climate change.

Speaking six months out from COP21 in Paris, Fatih Birol says that it is one of the most critical political meetings in decades. “When I look at the political picture, I see a momentum building and that’s good news.”

Last November there was an historic announcement between the leaders of China and the United States, with both countries announcing the determination to come up with an agreement in Paris on climate change. Birol stresses the significance of this announcement as these two countries account for almost half of global greenhouse gas emissions. In addition he highlights the EU 2030 targets that are already in place.

Birol adds that developing countries are also active on the climate change issue and they will come to Paris with commitments. “One tonne of CO₂ going to the atmosphere from Mumbai or Shanghai has the same impact.”

“More and more energy companies are starting to engage with the climate change issue, because to assume that climate policies will not affect the energy business is a mistake. Leaving aside the moral issue, it is a mistake from a business viewpoint.” Birol likens this to “assuming that interest rating will be the same for the next 25 years. A short sighted assumption in my view.”

The IEA has been active on the climate issue publishing the ‘World Energy Outlook Special Report 2015: Energy and Climate Change’ at the time of the conference. Birol observes that two thirds of greenhouse gas emissions comes from energy production and use. The report has a number of recommendations and details the IEA’s proposals for COP21.

2014: historic year

“I like to get my hands dirty with data,” says Birol. The latest IEA data shows 2014 was the first time in the last 40 years CO2 did not increase although the global economy grew. In the past there were only three occasions when CO2 did not increase and the reason was always, economic decline. Last year the global economy grew by 3 per cent and CO2 emissions did not increase. There are three main reasons for this:

1. The strong penetration of renewable energy;

2. The fruits of energy efficiency polices on the demand side; and

3. Chinese coal policy is becoming “more stick”, which has seen for the first time in 15 years a decline in coal consumption in China.

“Although almost everyone now agrees that climate change is a problem, why is it difficult to find a solution?” asks Birol. There continues to be disagreement about the share of responsibilities. Some say that we should look at the past trends and who was responsible for historic emissions. In the last 125 years the US and Europe have emitted more than 60 per cent of the global emissions. Looking to the future the contribution from emerging countries will be substantial. Emissions growth from China will be equal to emissions growth from the US, Europe and Japan combined. Emissions from India, a relatively poor country per capita, will soon overtake those of Japan.

Prompted by the UN many countries are now making commitments for emissions reductions, known as INDCs [intended nationally determined contributions]. Birol says that two thirds of global emissions are now covered by such agreements. “If these commitments are enacted, and governments don’t just pay lip service to them, they will have a real impact on the energy sector,” he adds.

He goes on to detail the impact of these commitments across the energy sector. One quarter of the world’s energy supply will be low carbon in 2030 if the commitments are achieved. Energy intensity will improve three times faster than in the last decade. Renewable energy will account for nearly 60 per cent of new capacity additions in the next 15 years in the power sector and two thirds of additional capacity will be in China, EU, US and India. China will be by far the largest contributor, with Chinese renewable energy investment greater than US, Europe and Japan combined. Oil growth will slow mainly as a result of improved fuel efficiency and natural gas will be the only fossil fuel that increases its share of the global energy mix.

Birol says the main challenge will be coal, which will get a “strong hit”. Total coal demand in the US, Europe and Japan will contract by 45 per cent and coal use in China and India will slow significantly.

“Climate change pledges for COP21 are the right first steps but they do not bring us to the 2°C target we need to reach.” Therefore the IEA report details four demands for the energy sector. “If the Paris agreement does not have these it risks being a failure,” he warns.

The IEA proposal for COP21 has four elements:

1. Peak in emissions around 2020: set the conditions which will achieve an early peak in global energy-related emissions;

2. Five-year revision: review contributions regularly, to test the scope to lift the level of ambition and to take account of technology changes;

3. Lock in the vision: translate the established climate goal into a collective long-term emissions goal;

4. Track the transition: establish a process for tracking energy sector achievements.

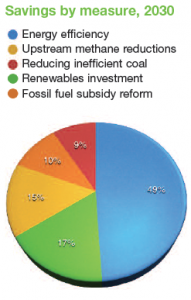

The peak in emissions in 2020 is the most important according to Birol. The current pledges slow emissions but don’t peak in 2020. The IEA report has a “Bridge scenario” which bridges current commitments and what needs to be done to achieve the 2°C target. There are five policies to make this bridge and they do not need any new technologies and they will also not harm economic growth.

In concluding, Birol stress that the pledges on climate change are not enough to achieve climate targets but they are a basis from which to “build ambition.” He warns energy companies that do not anticipate stronger energy and climate polices risk being at a competitive disadvantage. Looking forward to COP21, the IEA proposes four key energy sector outcomes, including a peak in emissions in 2020. In closing he highlights the fact that climate change will lead the agenda at the IEA’s Ministerial meeting in November, and stresses that climate policy will shape the future of the energy sector.