A force for change

Artist Rita Duffy talks to Owen McQuade about her work and her belief that art can be a force for change.

Artist Rita Duffy talks to Owen McQuade about her work and her belief that art can be a force for change.

Political art

I did a project in Texas, in a place called the Roe House projects, with underprivileged Afro-American kids and one of them said to me: “That’s all very well showing us what we can already see but how does that change anything?”

That conversation stayed with me for a long time. It is all very well artists recording or navigating what is going on in society but I have become much more interested in political art that points us in the direction of something better. That may sound a bit evangelical or missionary but I genuinely believe in art as a spiritual force, as a force for change that can offer society something better.

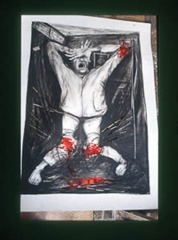

One of a series of 25-30 drawings I made through the 1980s. It was a kneecapping I witnessed in West Belfast and it now hangs in a museum in London.

I managed to get access to an AK47 which had been used in Northern Ireland. I moulded it into a work of chocolate. This AK47 – the freedom fighter’s weapon of choice – was that idea of the romantic hero and I wanted to subvert that.

Veil

Veil resulted from a conversation I had with an architect about a building with a lot of small rooms, which turned out to be Armagh Women’s Prison. I then visited the prison and couldn’t believe the weight of the doors of the cells. I managed to get six of these doors and in the studio I made this enclave. I wanted to say something of that internalised fear and grief that people can’t express when there is violence going on around them. For a lot of women their voice isn’t heard. There is a quiet despair at the core of that piece of work.

I wanted to do a project specifically about shirt making in Derry. It took 10 years and I got the opportunity to do the project in 2013. It was a project lead by contemporary art.

I wanted to give a voice to the labour of all the women in Derry over the century, who had built that city and yet they do not have a single public monument or endorsement of the labour they put into the city. I wanted to make pieces that were active and engaged. I fused the ideas of a museum, a contemporary art exhibition and a factory. I spent the first couple of months going around Derry looking in windows and poking in doors to try and get a sense of what was there, what happened, what is there. I went through the Tower Museum archive for a lot of imagery. I struggled with a lot of bureaucracy but I kept very focused. My idea was to employ possibly 10 women to actually work as a working, living art exhibition.

Here was this capital of culture and I wanted to make the shirt factory project to transform the city while it was there and to connect with the lives of women who had worked in those shirt factories. The women were employed to make things I designed, which we then sold in a shop. It was the sound of sewing machines once again in Derry.

I heard a lecture by Seamus Heaney on Paddy Kavanagh and on the way home I noticed the watch towers and came up with the idea that we should transform one of these watch towers into a work of art.

I wrote to the NIO and then got a call from a Colonel Harper who asked me: “Which watch tower did I want?” I managed to get inside one of the watch towers that looked down on the main Belfast- Dublin road, which sat on the hills that Cú Chulainn defended Ulster on. It was looking that this project might happen when it stopped – it is very hard to get anything done in Northern Ireland. I’m still hopeful that some day that the project will re-emerge.

112

Belfast-born Rita Duffy graduated in art from the University of Ulster. When asked how difficult was it to choose being an artist as a career, she replied: “My father was initially keen I do something like law but worked in engineering and had a fascination about how things worked. He encouraged me to draw and was very supportive and once I started selling paintings he thought it was great. My sister had gone off and done the big science thing, so I had the freedom to explore what I wanted to do. I was also very determined. I figured I could be half good at something someone else wanted me to do or I could be really good at something I wanted to do.”

In the 1980s after art school Rita became very interested in the work of German artists Otto Dix and George Grosz who painted “uncomfortable stuff” between the wars and were convinced they could bring about social change through their work. “I started making images that spoke to me about the historical situation and my personal situation in Ireland. I had that skill in painting and drawing and I wanted to create something uncomfortable. I think in a post-conflict society it is really important we engage with the arts and I don’t mean passively enjoy the Ulster Orchestra. I mean to have the courage to question what we do, who we are culturally and the complexities of that. This is the most interesting part of Ireland.”

Since the 1990s her work has been increasingly in a community context. “I started going out and engaging people, listening to them and hearing their experiences. I don’t believe you should just go into a community and ask everybody what they like. As an artist you have to lead. That’s not to say I impose work. I ask people to join me in a process of mutual respect to create a project.”

Rita has lectured on and taught art, mostly outside Northern Ireland, and has had exhibitions internationally in Europe and the USA.