Tackling economic inactivity

Northern Ireland’s high proportion of adults outside the workforce has held back economic progress over the last 30 years. Peter Cheney examines the scale of the problem and first strategy aimed at turning the situation around.

Northern Ireland’s high proportion of adults outside the workforce has held back economic progress over the last 30 years. Peter Cheney examines the scale of the problem and first strategy aimed at turning the situation around.

Economic inactivity attracts fewer headlines than unemployment but its scale is one of Northern Ireland’s most significant long-term problems. Simply put, the economically inactive are adults who are neither working (employed) nor looking for working (unemployed).

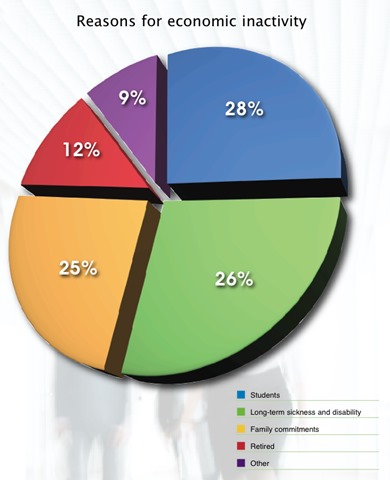

The economically active population is hard to picture because it takes in people in a wide variety of circumstances in life. A total of 563,000 people aged 16-64 currently fall within that definition. Four main categories stand out:

• 158,000 students;

• 146,000 people living with a long-term illness or a disability;

• 141,000 people looking after family members or the home; and

• 68,000 retired people.

The others include those with short-term injuries and illnesses, and also “discouraged workers” who would be considered unemployed by their friends and family but have given up on looking for a job.

As the list makes clear, inactivity is not wrong in itself.

Staying on at school, taking up further and higher education, starting a family and caring for relatives are voluntary and beneficial – both to those people and also society as a whole.

Focus

The Executive is focusing its attention on those people who would benefit from working. Being out of work, in turn, restricts their opportunities in life, results in them losing skills, and makes Northern Ireland’s economy less productive and less inclusive. Older people and single mothers are currently under-represented in the workforce.

Workless households are trapping “entire families into benefit dependency and persistent poverty”. If this “vast waste of human potential” is not tackled, it will hinder Northern Ireland’s economic development “for years to come”.

The strategy aims to help two key groups into work: people with long-term illnesses and disabilities; and lone parents. There will always, of course, be exceptions who cannot work e.g. mothers of very young children and the seriously ill.

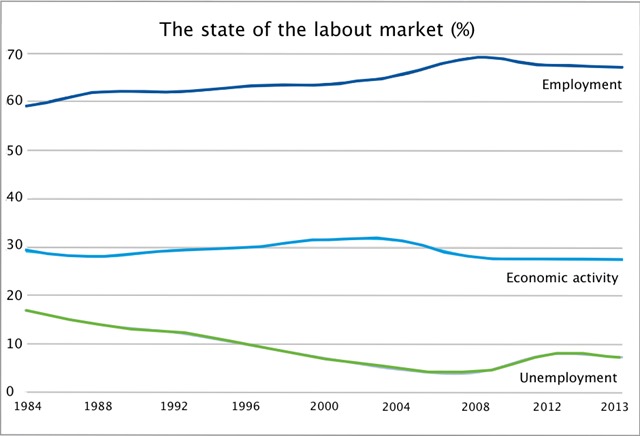

Northern Ireland’s economic inactivity rate – currently 27.2 per cent of the working age population – has consistently been the highest in the UK. Within the province, this varies between 21 per cent in Antrim and 36 per cent in Strabane, with Belfast and the western districts worst affected.

Northern Ireland’s economic inactivity rate – currently 27.2 per cent of the working age population – has consistently been the highest in the UK. Within the province, this varies between 21 per cent in Antrim and 36 per cent in Strabane, with Belfast and the western districts worst affected.

The national average is 22.2 per cent and the best performers are South East England (19.5 per cent) and Eastern England (19.9 per cent).

Inactivity has fluctuated around the 30 per cent mark since the first statistics came out in 1984. This, in turn, has had an obvious knock-on effect for Northern Ireland’s employment rate (currently 67.4 per cent). The Executive wants to raise this to over 70 per cent by 2023. While that would represent only a small percentage increase, it would make a significant difference in the lives of new employees, be an important symbol of economic progress, and take Northern Ireland out of the UK’s ‘bottom league’ of deprived regions.

An ‘economic inactivity strategy’ was promised in the 2011 Programme for Government and was published in draft form in December 2013. Employment and Learning Minister Stephen Farry has taken the lead and set out four strategic objectives:

1. help people with work-limiting health conditions and disabilities move into employment;

2. help lone parents currently receiving out-of-work benefits into employment;

3. reduce the number of people who leave the workforce; and

4. reduce the unemployment rate to pre-recession levels.

A specific task force, including civil servants, businesspeople and the voluntary and community sector, would hold departments to account for delivering the strategy. Practically, this will mean taking action on four different fronts:

1. promoting the value of work and increasing support to people entering the workforce;

2. increasing opportunities for employment and self-employment;

3. removing the “wider barriers” which keep people outside the labour market; and

4. preventing the problem by improving educational attainment and health.

Some of the first steps will involve commissioning new research into the effectiveness of efforts to reduce inactivity, with a view to improving outcomes. Pilot projects will also be set up to find new solutions. These could, for example, look at how to create work for people with few skills and also consider the different reasons for inactivity in urban and rural areas.

Barriers

Depression and other mental health conditions are the dominant reasons for people claiming health-related out-of-work benefits. These account for 45 per cent of claims for employment and support allowance claimants and 47 per cent of claims for incapacity benefit. Most of those who claim these benefits are male and aged over 40.

Older workers are a particular priority as they have less time before retirement, are often stereotyped as incapable of work and are less likely to be employed than their counterparts in Great Britain. An older worker, though, will obviously have up to three times as much practical life experience than a school leaver or recent graduate.

A different picture emerges among people with full-time family commitments. Most carers (60 per cent) are female although men make up a significant share as well. The vast majority of single parents are female: 98 per cent. The age distribution is more even and therefore includes more people in their 20s and 30s who are usually better qualified than older workers.

Lack of motivation is a major obstacle across both groups: eight out of 10 do not want to work. The Department for Social Development’s benefits and tax credits survey – published in 2012 – indicated that this is mainly due to a lack of confidence rather than an outright refusal to work. Claimants generally thought that they were incapable of work or that no-one would give them a job.

Poor health and fears about their inability to balance work and family life were also mentioned. A small minority (10-16 per cent) either said that earning their own money was not important or that they enjoyed living on benefits.

The different characteristics of those groups imply that a range of jobs are needed in order to provide an “entry point” into employment. However, this is only a starting point. New employees will need to keep building up their skills if they want to keep their jobs. The proportion of low skilled jobs is constantly going down as the global economy demands higher skills.

“It should be recognised that this attempt to reduce economic inactivity is unprecedented,” the strategy adds. The 70 per cent goal is “ambitious, yet it is achievable”. Progress partly depends on economic conditions but also on the Executive’s own momentum in delivering its 12-point action plan.

“It should be recognised that this attempt to reduce economic inactivity is unprecedented,” the strategy adds. The 70 per cent goal is “ambitious, yet it is achievable”. Progress partly depends on economic conditions but also on the Executive’s own momentum in delivering its 12-point action plan.

Four departments (led by their ministers) will be responsible for rolling it out:

• the Department for Employment and Learning (Stephen Farry);

• the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (Arlene Foster);

• the Department for Social Development (Nelson McCausland); and

• the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (Edwin Poots).

The first point is to establish the taskforce. Six of the other points involve commissioning more research and this will cover what services are being provided by government, the impact of welfare reform, and how much low-skilled work is available in the Northern Ireland economy.

Further actions cover the pilot projects, a better support and incentives package for employers, appointing “corporate champions” who can affirm the role played by older workers, and a stronger emphasis on promoting good mental health in the workplace.

The consultation closes on 17 April and a final strategy is expected before the summer. Minister Farry has a strong personal interest in the subject and the first actions can therefore be expected later this year.

“Government alone does not have all the answers,” he told the Assembly in December and he encouraged everyone with an interest in economic inactivity to consider his proposals and make their views known.

Farry also had a word of caution: “I cannot overemphasise the fact that there is no quick-fix solution to the problem.” He added: “There are many individuals who, for a range of complex personal and health reasons, will never be able to fully engage with the labour market. However, there are also many individuals who, with the right level of support, will be able to participate in some meaningful work.”

The desired result – “a more buoyant and competitive labour market” – would in turn bring wider benefits to Northern Ireland’s economy and society.

The draft strategy is available at www.delni.gov.uk and comments can be emailed to economicinactivityconsultation@delni.gov.uk