WTO tariffs explained

Failure to successfully conclude negotiations on the terms of a trade deal with the rest of the EU before Britain’s forthcoming departure from the customs union could force the UK to revert to World Trade Organisation rules. agendaNi examines.

A trade tariff is a customs duty or a tax on imported goods. While many countries have sought to reduce tariffs and other barriers to trade over the past century, often through multilateral agreements, they are most commonly adopted in an effort to protect developing economies and domestic employment, while in more developed countries they can safeguard vital industries. There are three main tariff scenarios within the WTO option: most favoured nation (MFN) tariffs, preferential tariffs and bound tariffs.

- A MFN tariff is one which WTO members agree to apply to all trade partners who are simultaneously fellow members. In practice this means that MFN tariffs are the highest rates that WTO members apply to each other.

- Preferential tariffs are essentially agreements made between countries in which they agree to charge a rate lower than the MFN rate. In a customs union, these rates can be agreed upon and set at a reciprocal level, often on almost zero across all products. This varies between trading partners and agreements. Many countries will provide developing nations with unilateral preferential tariffs, rather than reciprocal agreements.

- The bound tariff is the maximum MFN tariff applied to a commodity line by individual WTO members. When countries join the WTO or negotiate tariff levels, the top level, bound tariff rates, are agreed rather than specific individual rates. As such, in practice, bound tariffs are not necessarily applied by WTO members towards each other. Instead they have flexibility to increase or decrease tariffs within the parameters of the bound level. The gap between the bound and the MFN applied is called the binding overhang. If this overhang is large, then a member’s trade policy has the potential to be less predictable.

Within the EU, a Common Customs Tariff (CCT) is applied to all goods imported across its external border from the rest of the world. While the tariff is common, rates of duty alternate in correlation with the economic sensitivity of the goods. The tariff is a combination of goods classification and the duty rates which apply to each classification. CCT is uniformly applied to ensure that domestic producers can compete in the internal market with third country exporters.

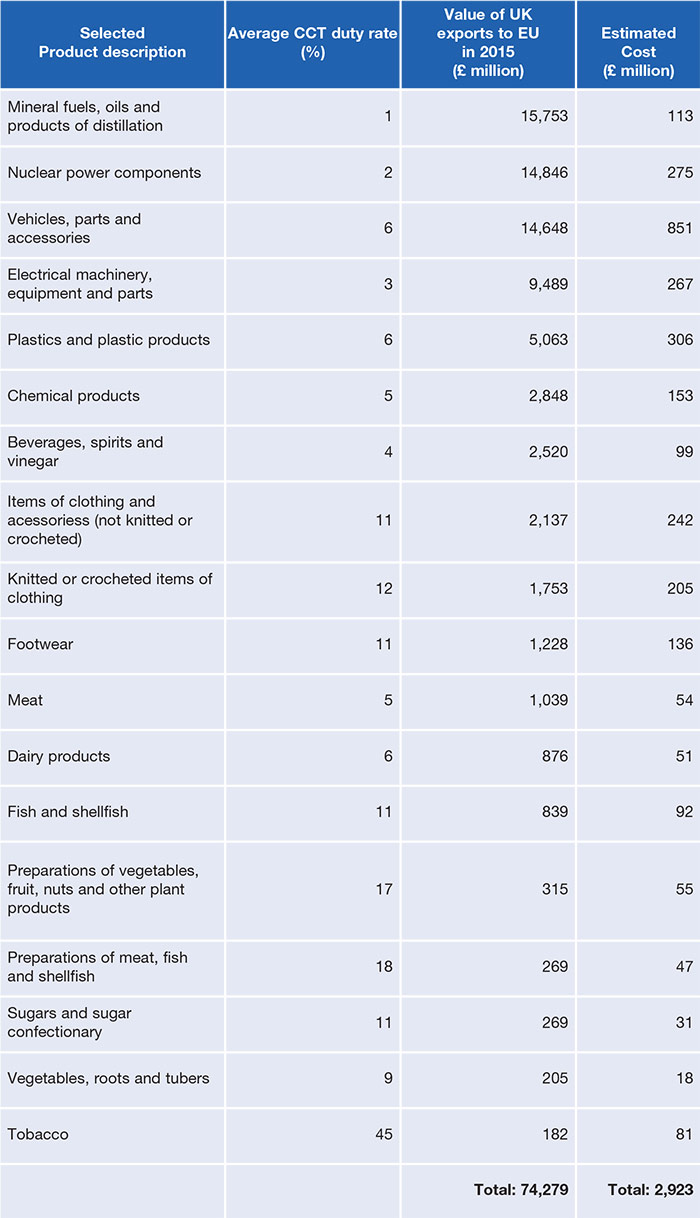

If the British Government fails to secure a trade deal with the rest of the EU before the UK completes its exit, it will be forced to trade under WTO rules. Thus, British exports would trade into the CCT, pushing up prices and undermining competitiveness. Confronted by an average tariff of 4.8 per cent, exporters would be faced with a choice: either maintain prices, absorb the reduced competitiveness and experience decreased sales or reduce product prices to recoup the competitive edge in spite of a reduced profit.

The EU tariff rates are swingeing, ranging from zero per cent on pharmaceutical goods to 45 per cent on tobacco. As such, some export industries are more exposed than others. UK exports would also face non-tariff barriers (NTBs), including market standards and regulation, when trading into the EU. In a worst-case scenario, any subsequent reduction in exports lowers an ability to pay for imports, reducing productivity and therefore has the potential to trigger a decline in living standards.

Exiting the EU without securing a free trade deal with the other 27 member states would simultaneously initiate a departure from over 50 trade deals that the EU has secured with countries across the world. Likewise, exceeding tariff-rate quotas for agricultural produce can induce much higher rates of duty than those detailed in the adjoined table.

However, at the same time, the present depreciation of sterling would act as a counterbalance to a reduced competitiveness provoked by the proliferated cost of importing British goods. The symptoms of a squeezed export market could be alleviated by securing cheaper imports through a unilateral decision to drop all import tariffs and move to free trade. In theory, consumers would experience net gain, as would manufacturers, while all sectors would be exposed to competition, thereby enhancing industry dynamism as trade shifted to correlate along lines of strength.