The Curragh mutiny

A key centenary marked the time when Irish unionist officers defied the Cabinet over home rule.

A key centenary marked the time when Irish unionist officers defied the Cabinet over home rule.

As the home rule crisis developed in 1914, the Curragh mutiny posed a direct challenge to the British Government’s authority and brought the loyalty of its army into question. The incident was not a mutiny per se as it involved senior officers although historians consider ‘mutiny’ as the most accurate description for what took place.

Unionist leaders had formed an Ulster provisional government but Winston Churchill (then First Lord of the Admiralty) dismissed this move as “a treasonable conspiracy” at a speech in Bradford on 14 March. Churchill planned a show of strength to force the UVF to back down. Officers who refused to obey orders would be immediately dismissed although those living in Ulster would be not be obliged to take part in the operation.

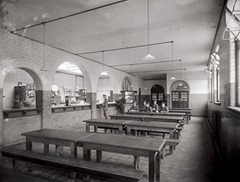

The Commander-in-Chief in Ireland, Sir Arthur Paget, passed on the Government’s instructions to officers at his headquarters – the Curragh camp – on 20 March. Fifty-eight officers, including the commander of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, Hubert Gough, stated they would refuse to march into Ulster.

Gough demanded a written guarantee the army would not be used to coerce Ulster. The idea came from Sir Henry Wilson, the army’s Director of Military Operations.

The Cabinet approved a statement but Gough claimed that it was ambiguous. His preferred wording was “the troops under our command will not be called upon to enforce the present Home Rule Bill on Ulster” and this was supported in writing by Sir John French, the Chief of Imperial General Staff. French and War Secretary John Seely were both forced to resign.

The officers who led and supported the mutiny were southern unionists, who saw home rule as a surrender to nationalists, but some of their colleagues were sympathetic to home rule. A Major P Howell wrote: “If we do anything at all it must clearly be for ‘law and order’ and nothing else.” Howell was “in principle … a home ruler and not swept away by Ulster heroics” but thought that Paget had been tactless in how he handled the situation.

All of the key players served in the First World War. Paget was demoted and retired when the war ended. Gough went on to enjoy a long business career.

Wilson became the Northern Ireland Government’s security advisor and was elected as Westminster MP for North Down in 1922. He was assassinated by the IRA shortly afterwards. French became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and survived an IRA assassination attempt in 1919.

Seely continued his career in Parliament but was discredited for supporting appeasement in the 1930s. Churchill, in the long term, emerged as the most successful British politician of the century.

The Curragh mutiny weakened the army’s credibility and was followed by the UVF’s Larne gunrunning on 24-25 April. The sense of crisis continued to build throughout 1914 until war in Europe resulted in home rule’s suspension.

The Curragh was transferred to the Free State Army in 1922 and now serves as the main training camp for the Irish Defence Forces.

Reflecting on the incident, UUP leader Mike Nesbitt said that it “immeasurably weakened” John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party “and highlighted how difficult it would have been to impose an unwanted constitutional settlement on the people of what is now Northern Ireland.”

Trinity College historian Eunan O’Halpin commented that if generals could “pick and choose” which parliamentary decisions to obey “then the entire fabric of the British constitution would be torn to shreds.” These issues were “never teased out” and the Curragh mutiny was “largely forgotten in the grand narrative of 20th century British history.”