A review of Fortnight

Following its closure, Peter Cheney reviews the history of Fortnight magazine and gathers a former editor’s views on the state of Northern Ireland journalism today.

Following its closure, Peter Cheney reviews the history of Fortnight magazine and gathers a former editor’s views on the state of Northern Ireland journalism today.

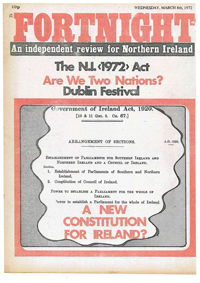

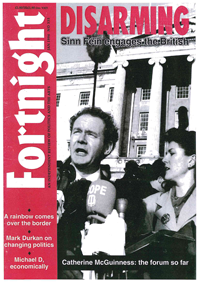

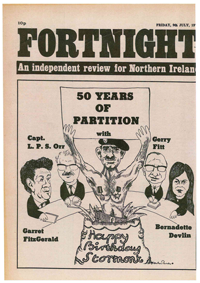

An era of political journalism has ended with the demise of Fortnight. The political and literary magazine was originally founded in 1970 to forge a middle way with a liberal and left-wing slant and documented the long twists and turns of the Troubles and peace process.

“Fortnight has served its time,” the last leader column read. “Over the forty years since we started in 1970, we have tried to give space to all sides to make positive contributions to our shared problems. We have also attempted to make sensible suggestions of our own on what might help to resolve our difficulties in living together in a divided society, caught by history between two more or less sovereign states and nationalities.”

Contributors have ranged from Mary Robinson to Peter Robinson, Malachi O’Doherty to Billy Hutchinson. Tom Hadden was its first editor (from 25 September 1970 to October 1976), succeeded by Ciaran McKeown and then an assorted editorial committee in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Andy Pollak took over as editor in January 1982, followed by Lesley Van Slyke (1985-1986) and Robin Wilson (1986-1995), John O’Farrell (1995-2000), Malachi O’Doherty (2002-2006) and Rudie Goldsmith from then onwards.

All back issues are available online through the JSTOR archive: www.jstor.org

All back issues are available online through the JSTOR archive: www.jstor.org

John O’Farrell had previously been its de facto Dublin correspondent since 1992, writing about the arts when Michael D Higgins was the Republic’s Arts Minister. He had moved in Belfast in 1994, to do a masters at Queen’s, and “to my amazement” was appointed editor when Robin Wilson left to set up the Democratic Dialogue think tank.

O’Farrell balanced writing and editing with chasing funding and dealing with creditors and the tax man: essential for keeping the business afloat.

“Highlights were all to do with journalism, learning my trade and getting access to these amazing events particularly around the time of the Good Friday Agreement,” he recalls. “The lowlights were dealing with the day-to-day survival issues of a magazine with no money.”

He particularly enjoyed finding and encouraging new writers: “a pool of people who had very strong opinions on all kinds of different issues and were prepared to write wonderful copy for nothing.”

Fortnight set out to “buck the consensus on a lot of things”. Radical republican and hardline loyalist views on the same issue sat side by side. It also raised subjects such as abortion and drugs which were “a bit taboo”, campaigned for a bill of rights and integrated education, and added an internationalist perspective. What could, for instance, be learnt from the Åland Islands (a Swedish populated part of Finland) or indeed the more extreme conflicts in Bosnia and South Africa?

The magazine began in the “golden age” of political magazines but was ultimately finished off by the internet, where a reader can pick and choose websites to suit their own tastes.

Former Queen’s University politics lecturer Sydney Elliott saw it as a “journal of record” and a “mixed bag”. The sidelines about who was seen meeting whom were of most interest to him, the poetry less so.

Former Queen’s University politics lecturer Sydney Elliott saw it as a “journal of record” and a “mixed bag”. The sidelines about who was seen meeting whom were of most interest to him, the poetry less so.

“The role of it was essentially an independent view of politics in Northern Ireland,” he recalls, “and it probably would have brought together viewpoints there which were academic and which you wouldn’t have found in any other place.”

It also “seemed to exist on a shoestring”. He remembers walking up a rickety staircase in its Lower Crescent office and also seeing Martin O’Hagan working late on copy one Sunday night. O’Hagan was later murdered by the LVF in 2001.

Elliott continued to buy Fortnight but found it had disappeared from the shelves late last year. He was disappointed with its closure but notes that it was “maybe something that needed to change radically” to stay relevant.

Churnalism

Looking at the province’s political media today, O’Farrell regrets its lack of depth when journalists could dig into plenty of topics for more of a story: “Most media organisations have laid off almost all their experienced journalists. You don’t have specialists anymore.”

Instead, a smaller corps of younger journalists is under more deadline pressure than ever before. More people now work in PR than full-time journalism.

“Cut and paste” stories are common (also termed ‘churnalism’) and too many reports are taken “at face value”.

“Cut and paste” stories are common (also termed ‘churnalism’) and too many reports are taken “at face value”.

The narrative of cutting corporation tax “sounds good” as a story but many of its supporters stand to gain from the move. Separately, pursuing Stephen Hester and Fred Goodwin over their bonuses and Goodwin’s knighthood produces “a little moral fable about good and bad people” rather than a more complicated story about politics, money and where power lies in society.

Many journalists, he warns, think that balance means sourcing two opinions, to give both sides of the story, rather than checking the facts and statistics and establishing what is true. The worst example, in his view, is the “so-called debate” on global warming, where the established scientific view is balanced by sceptics who are sponsored by vested interests.

As for the solution, it lies in “more journalists with more time to properly investigate and research stories.” News stories must focus on news “in other words facts rather than opinions” which could be as ignorant as the other. Journalists should “assume that the people who read [their copy] are even more clever than you are” and treat readers as “citizens not consumers”.

All media outlets have a moral responsibility to serve the public. The worrying alternative is a “very shallow competition based on sensationalism.”

“It’s a shame that it’s gone,” O’Farrell reflects on his former mag. Young people will miss the thrill of “seeing your name in print and in a by-line in a magazine that you know is read by important people” in Northern Ireland’s political class and cultural élite.